Health and social change – a comparative perspective

Michael 2004; 1: 145–162

Neither ‘health’ nor ‘social change’ is an easy concept to define in a precise way. For most contemporary scholars, health is not the opposite of disease, even if disease is the most obvious threat to health. One can very well imagine a person having relatively good health in spite of being ill. Conversely, a person may lack important elements constituting good health, without being medically diagnosed with a disease. Let me – in this context – suggest a definition of health, which is a bit wider than the «biomedical» model. In WHO’s famous words, ‘health’ is related to ‘well being’ – ‘complete health’ meaning ‘complete well being’. In the context of social change, I would prefer a more limited range, where health is one’s physical and mental capacity to realise reasonable vital goals of life. Otherwise, temporary feelings of sadness (for instance among Swedes who are not able to beat South African high jumpers in the world championship) would be signs of bad health. Nor may inherited physical and mental handicaps necessarily be defined as bad health per se. It depends on how much the handicap threatens the vital goals in a given context.

Keynote speeker Jan Sundin (Linköping) and Petr Svobodny (Prague). (Photo: Ø. Larsen)

Health will – by this definition – also depend on the cultural, economic, social and political circumstances in which one is living. The culturally changing definitions of health will depend on what is considered to be reasonable goals of life. A lack of socio-economic resources is not a lack of health itself, but it will often be an obstacle to good health (good physical and mental resources given one’s genetic heritage) and therefore prevent one from fulfilling the vital goals of life. The possibilities to realise these vital goals will depend on the socio-economic resources of society and of oneself within this structure, including the politically shaped resources or obstacles for good health.

This leads to an image of health and society (either on the structural level or for a certain individual) as a mutual relationship between different types of resources, which are together identical with a great part of what we call ‘welfare’. Health is both a resource for the creation of other resources and dependent on these resources – both the health of one person and «the people’s health». Everything from genetics to culture influences health. What needs to be discussed in this context is its relation to the social fabric and the way it changes.

We are, given these starting points, forced to reduce the complexity and multitude of factors when trying to uncover the network of factors and interdependencies. We must be aware of the difference – and interplay – between the effects of social change on single individuals versus the effects on the whole society or groups within the society. Some of these effects can be measure by quantities, percentages, as chances or risks characterizing populations. Other effects have to be analysed in a qualitative way, comparing one system with another. Given that health depends on a number of socio-economic resources, allow me to present some relatively simple statements with graphics from 19th century Sweden as examples of my own understanding of health and social change.

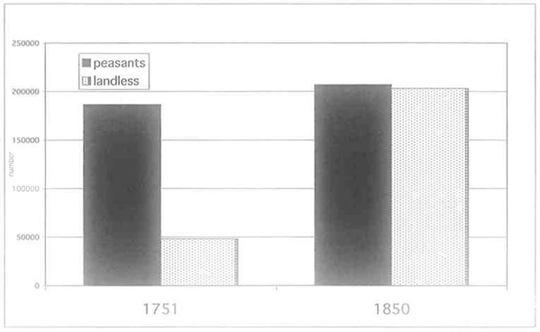

Fig 1. Number of heads of household in the Swedish countryside among farmers and landless persons.

Source: Sundin and Willner 2003, p 31.

Changes in the labour market, social structure and social security systems put a heavy burden on people’s occupational flexibility, social adaptability, and ability to find economic safety for themselves and their families.

Theoretically and as far as data allow us to prove it, basic material conditions are closely linked to health. To get a decently paid work and social security are two essential elements for safety and health. Changes force people to find new ways in order to acquire those resources, a challenge for those affected. Figure 1 illustrates the transition of Sweden from a predominantly agrarian society with a majority of households of farmers, their kin and servants in mid-eighteenth century. One century later, the landless population, relying on casual employment and with limited social security, had grown drastically and constituted almost 50 % of all households. The reason for its growth was twofold: population growth caused by declining mortality parallel to the rationalisation of agriculture, creating a surplus of people looking for work. The result was circular migration of young men and women in rural areas and into the still small and pre-industrial cities, often surviving on a day-to-day basis.

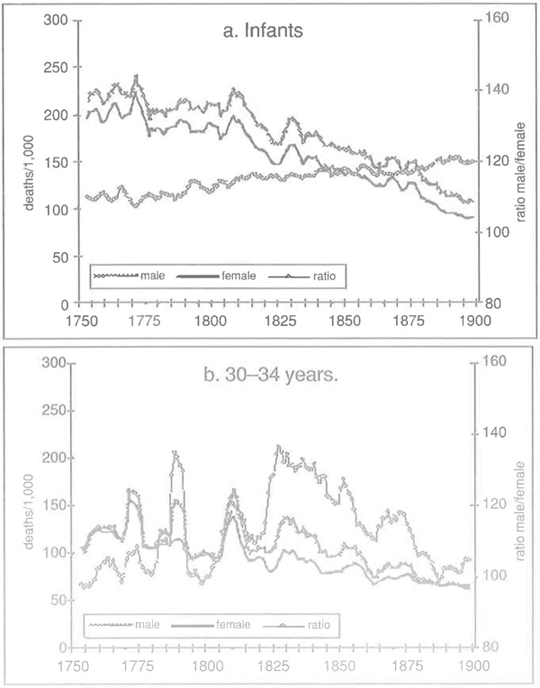

Figure 2. Infant mortality (a) and mortality 30–34 years (b) in Sweden 1750–1900.

Source: Sundin and Willner 2003, p. 36f

Transitions that are fundamental and rapid often have immediate, profound effects on health.

Social change takes place all the time and everywhere. Some changes are less dramatic, some are relatively slow, giving individuals and collectives the possibility to adapt and find new ways to realise the good life. Not surprisingly, profound and rapid changes have – as empirical evidence suggests – visible effects on health as well. Not all changes are of course negative for health. People in growing economies tend to become healthier. Some changes have been positive in the long run, while they have had negative effects for parts of the population during the initial phases.

What, then, did the social and economic transition mean to the people’s health in early nineteenth-century Sweden? As a matter of fact, the crude mortality rate declined steadily after 1810, indicating a substantial improvement of their health in spite of economic and social restraints. However, dividing the figures by age and sex in Figure 2 reveals a more complex situation. Infant, child and adult female mortality went down simultaneously, while adult men did not prosper from the same positive development.

Welfare and health also depend on gender, age, and social class.

Generally, enough evidence has been produced to show that gender differences of health or mortality are not exclusively – or even mainly – depending on genetic factors. In many societies where there is a certain degree of equity between the sexes, adult males tend to suffer more than women, especially from lethal health problems. A large part of this surplus mortality is caused by male behaviour – excessive drinking, heavy smoking, drug abuse, violence or other types of risk behaviour. Gender – culturally constructed roles – is in several ways the mediating factor between society and sex specific mortality. Since gender roles are linked to age and class, all three factors contribute to case specific health patterns. Being a relatively poor, unmarried, middle aged man in an urban influx area during periods of rapid social change does, for instance, seem to fit badly with the male gender role, increasing health risks.

So, if we are looking for a group that was particularly vulnerable to the changes taking place during this period of time in Sweden that is where we should find it. And data confirms our expectations. Men were not in general in an economically worse situation – probably on the contrary. They usually earned more than women, and yet the expected differentials caused by class and civil status were greater among men than among women, particularly in the urban areas.

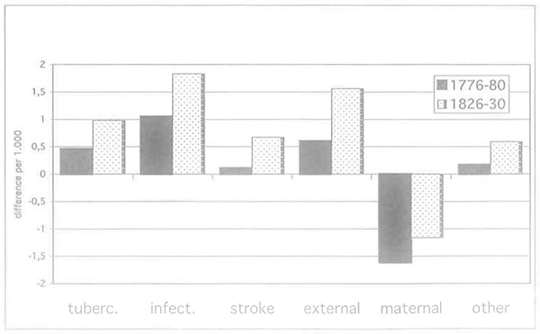

Figure 3. Sex differential causes of death, 25–49 years of age, in Sweden 1776–80 and 1826–30. 0 = no difference; 1 = 100 % difference, etc. Male surplus above 0-line, female surplus below 0-line.

Source: Sundin and Willner 2003, p. 40.

Cultural and gender factors within a particular epidemiological setting often have different effects on the health of men and women.

Although there seems to be a certain tendency for men to run the highest risks, cultural patters – for instance in highly traditional patriarchal societies – may change mortality patterns, making women more vulnerable. HIV/AIDS shows that this can be particularly dangerous in a certain epidemiological milieu. However, in the Swedish case 200 years ago, the result is in line with the more general pattern. Cause-specific mortality based on the categories reported in contemporary death statistics, is not always easy to interpret. The story told in Figure 3 is, however, consistent enough. Male surplus mortality and its increase existed in all groups except maternal deaths both in the 1770’s and 50 years later. The very high male figures for «external causes» (accidents, assaults, suicide, etc.) is particularly striking and congruent to similar patterns in today’s examples of rapid social change. The figures indicate that a common factor influenced most types of mortal diseases and – at the same time – hazardous male lifestyles.

Figure 4. Deaths caused by acute alcohol intoxication in Sweden 1804–1870 according to death registers and autopsies.

Source: Sundin and Willner 2003, p.43.

If social and geographical mobility increases, some people benefit while others lose out.

During rapid changes, old norms, rules and institutions no longer function as efficiently as they did before.

New economical structures mean that old jobs disappear and – at the best – new jobs are offered elsewhere with new skill requirements. Geographical and social mobility tend to increase, a chance of improvement for some but a risk of failure for others. The more dramatic these changes are, the higher the risk of failures. While the ‘winners’ may benefit materially and feel safe and satisfied, the ‘losers’ may suffer. In the end, the latter affects health negatively in a diversified way: from economically and psychologically induced problems to behaviour that is directly or indirectly negative for the health of oneself or others: starvation, alcoholism, smoking, externally caused health problems, etc.

The way to individual safety is regulated by customary norms and rules: what kind of skill to acquire, how to behave, where to go for help, etc. Formal and informal institutions exist in order to regulate this process and traditional ways are often not fit for new socio-economic circumstances. In addition, a new social context usually means that even norms that are not directly related to the material sector are changing, increasing the risk of confusion and ‘anomy’ in Durkheim’s sense of the word – a psychosocial process.

A large part of the generation of men born in farmers’ households in nineteenth century Sweden found that they would probably not manage to settle safely on a farm of their own. Other men were sons of the landless population and had small chances to move upwards socially. These men (and women in the same generation) went as servants from one place to another, some of them ending up in urban areas with equally small opportunities for social advancement or even a steady job. The skills and norms they were accustomed to do not fit very well to the new circumstances. Marriage was postponed due to the lack of basic means. Many females had their first child outside marriage without fathers who wanted to take the responsibility for their offspring. The men had difficulties to fill the central traditional role as breadwinners. Local supportive informal networks and social control were not as strong in the urban, more anonymous, milieu. Women seemed to be able to handle this better, even if many spinsters and widows had to rely on the meagre supply of poor relief already in their forties. The parallel humps in male surplus mortality and in deaths caused by acute alcohol intoxication in early-nineteenth Sweden in Figure 4 are Striking but certainly not a coincidence. They are probably just showing the tip of an iceberg with direct or indirect effects of harmful male lifestyles.

These negative effects, even when change is positive in the long run, have sometimes been summarized as «social stress».

In the contemporary affluent part of the world, social stress has become a popular label for the negative psycho-social effects of a person’s inability to cope with a situation where external demands and internal aspirations and hopes are not satisfied at work or in general. Social stress has, however, also been used as a diagnosis for societies where rapid social change make these tendencies endemic and can no doubt be used in that sense even to describe historical examples.

The impact of change is always filtered through formal and informal institutions.

Formal and informal institutions are creating the rules of the social life, hence having an impact on welfare and health. Some institutions are, directly or indirectly, established in order to minimise social dysfunctions such as poverty, health risks and social problems in general. The way these institutions function decides the potentials to strengthen the resources that are essential for welfare or to counter negative effects of social change. Much changed during the Swedish transition from the old «peasant» world. But other traditions survived or developed, some to the benefit of the people’s health. Ideas emanating from Enlightenment that disease could be fought with empirical knowledge and prevention prevailed and were realised in several ways. Slowly, the number of district physicians grew in order to serve a sparsely populated country. They were assisted by a new type of midwives, trained and «indoctrinated» in order to teach breastfeeding and childcare. Mass vaccination against smallpox was quickly introduced in the first years of the nineteenth century. The success of this campaign was possible because of the support of efficient parish administrations, headed by the vicar in collaboration with the local elites. Campaigns for cleaner cities – advocated by physicians – were slowly accepted by the city magistrates, which decreased the risks of gastro-intestinal infections and increased life-chances for infants.

These are interventions by the state as a local and central agent for health, forcing the mortality curve downwards. But why did this bring down mortalily, among adult women but not among men? The most plausible explanation is that the female gender role was more flexible in the face of social problems. One issue, which remained unsolved until the era of industrialisation and emigration in the second half of the century, was what contemporary observers called «the social question». It represented unemployment, poverty, uprooted communities and social conflicts, something that women in certain respects coped with better than men. One of the potential factors that may have been to the advantage of women, due to their gender roles, is «social capital». This term is used in many different contexts with different definitions and connotations. Below, it is primarily seen as resources emanating from people’s belonging to, ability to invest in, and capitalise support and safety from dose human relationships.

Informal institutions – as voluntary associations, social networks in the workplace or among neighbours, the family, and other primary groups – and the way civil society functions are essential for social stability and security.

-

«Social capital» is one factor that determines who will become winners and losers.

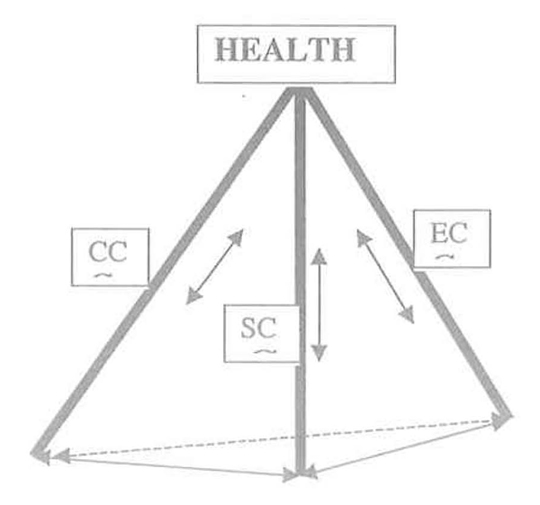

Figure 5. Health, economic capital (EC), cultural capital (CC) and social capital (SC).

Although money and its material equivalents to some extent are necessary assets and solve many resource problems, it is not the only means for safety, welfare and health. What has been called ‘social capital’ – in its different definitions and appearances – can be a positive resource to uphold and restore health. This concept can be used both/either as an individual or a collective resource. It may carry more or less weight and importance in specific cases. Although it has an impact both for rich and poor, it is logical to assume that social capital is particularly important for the welfare and health of those who are vulnerable and living close to the limit of material necessity. Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between cultural and social capital and his emphasis on the possibility to exchange one type of capital for another is illustrated in the model of three pillars (types of capital) supporting health in Figure 5. The inter-relationship between the four corners of the pyramid is important. Strengthening or weakening one of the four corners has positive or negative impacts on the strength of the other three. This model must of course be used specifically for each context and often analysed separately for men or women.

Public institutions can distribute and redistribute material resources, welfare, and social capital.

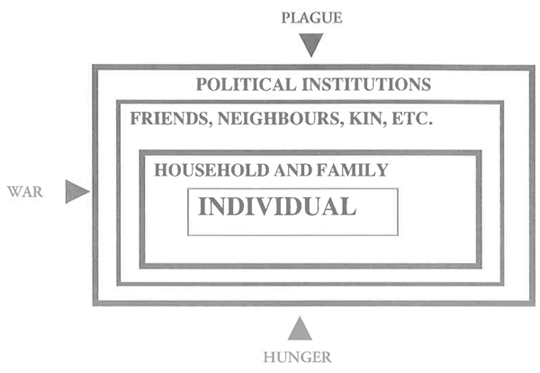

This introduces the crucial role of politics, policy and political institutions in the shaping of welfare and health for individuals and the people. It is evident that informal networks, guilds, and other non-state institutions have been essential for people’s safety in the past. Yet, even if persons and groups had to handle these things within a less organised state in l’ancien regime Europe, historians have increasingly found that there were already by then a number of such tasks taken care of by local political bodies, a form of early «linking social capital», where the elite tries to enhance the social resources of its citizens. The welfare state signifies the ambitious attempt to realise this vision. The role of public institutions during social change is a challenging task. Equally, political change and dismantling or building new institutions may be the spark changing the social fabric. In extreme systems – for instance the apartheid state – institutions reinforce political, economic and social inequality and thereby inequality in health. In a crude sense, it is of course true that our societies have changed from a community based «Gemeinschaft» with strong close links between individuals to a «Gesellschaft» with formal institutions taking care of our needs. It is, however, also true that the community model has never been completely wiped away. Further more, a blend of the two models is probably optimal. The community needs a protective and benevolent state and the state will function badly if the community is weak. Figure 6 illustrates the strong Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft attacked by three classical threats to health.

Figure 6. The strong society – strong community model

Conclusion

Social change is the changing conditions for fulfilling certain vital goals in life, above all those related to safety – materially and psychologically. Economic resources are created within a certain mode of production (not necessarily referring to Marxist theory). In the human society, the distribution of these resources is organised within a social system, created by norms, rules and institutions. The mode of production has implications for the social system, like a certain social system has implications for the way economic resources are/can be produced. Political change may change the rules and conditions for both economic and social systems. We are sometimes unable to decide if there is a casual chain of events leading to the outcome, at other times economic or political change have obviously come first. Table 1 lists factors observable in nineteenth-century Sweden and in contemporary Russia and South Africa. The contexts are indeed far away from each other in time and space, and yet we can identify similar patterns.

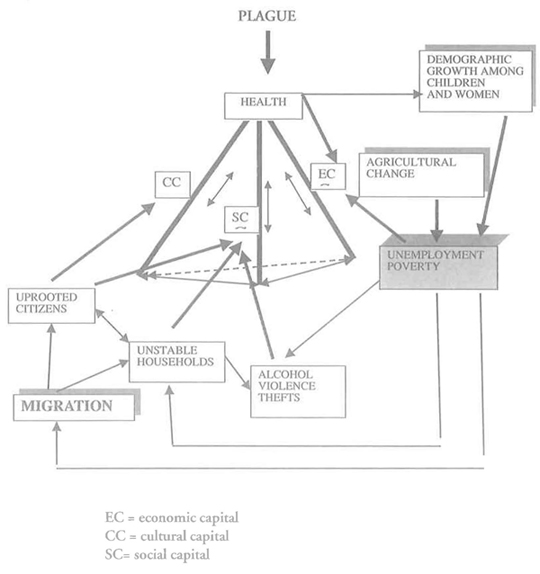

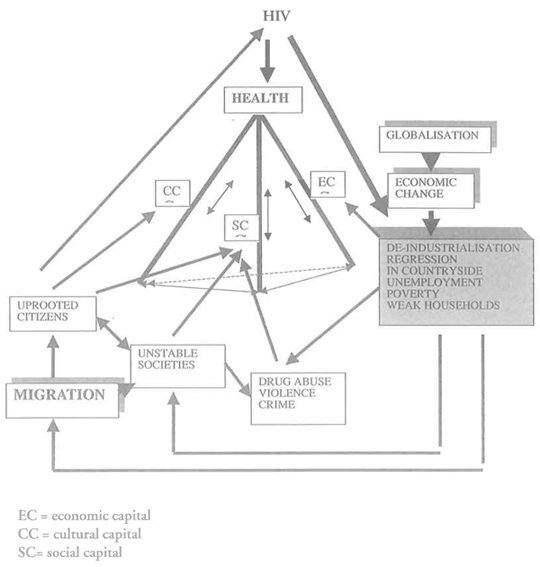

Two provisional «scenarios» are presented in Figures 7 and 8. They give a «reductionistic» picture of relations between health and social change in nineteenth-century Sweden and contemporary South Africa. These scenarios are not deducted from a pretentious theory. They are rather empirically based arguments for comparative analysis of the way social systems function in periods of change.

Amongst other worthy things, it is necessary to increase our understanding of who become winners and who become losers in the perpetual distribution and re-distribution of resources for human welfare and health.

Therefore:

It is necessary to acknowledge the complexity of context-dependent factors in an analysis of health and social change. Single observations of statistical correlations between a few variables may put the attention to intriguing questions. Used for simplified answers they could be more misleading than enlightening.

-

However, even in complex cases, reality must be reduced and the most important elements and events must be identified. Provisional scenarios, based on the experience of other events with similar patterns, are one of the ways. Neither over-simplification nor ad hoc explanations help us to real understanding.

Table 1. Factors connected with health and social change in 19th Century Sweden and Russia and South Africa today. Factor

19th C.Sweden

Russia

RSA

Political change

Moderate

Yes

Yes

Economic & Social Change

Changes in production

Yes

Yes

Yes

Changes in agriculture

Yes

Yes

Yes

De-industrialization

No

Yes

Yes

Employment crisis

Little industrialisation

Yes

Yes

Pauperisation

Yes

Yes

Yes

Increased inequality

Yes

Yes

Yes

Welfare provision crisis

Yes

Yes

Yes

Demographic Change

Population size:

Up

Stable?

Stable?

Migration to cities

Yes

Yes

Yes

Infant & child mortality

Down

Stable>up

Stable>up

Adult female mortality

Down

Stable

Up

Adult male mortality

Up

Up

Up

Family/household structure

Crisis

Crisis

Crisis

Epidemiological change

STD’s/HIV

STD’s high

HIV up

HIV up

Tuberculosis

High

Up

High>up

Other infectious diseases

High>down

Low>up

High>?

Health differentials

By gender

Yes

Yes

Yes

By marital status

Yes

Yes

Yes?

By class/ethnicity/»race»

Yes

Yes

Yes

By region

Yes

Yes

Yes

Urban/rural

Yes

Yes

Yes

Socio-cultural change

Uprooted societies

Yes

Yes

Yes

Norm crisis

Yes

Yes

Yes

Social losers’

Yes

Yes

Yes

Abuse of alcohol and drugs

Up

Up

Up?

Violence

Up

Up

Up?

juvenile delinquency

Up

Up

Up?

Other crimes

Up

Up

Up?

Summary

Political change

Moderate

Yes

Yes

Economic & social change

Yes

Yes

Yes

Demographic change

Yes

Yes

Yes

Epidemiological change:

Yes

Yes

Yes

Health differentials

Yes

Yes

Yes

Socio-cultural change

Yes

Yes

Yes

Figure 7. Health and social Change – Sweden c. 1800–1850.

Figure 8. Health, capital and social change: South Africa 2002

REFERENCES

Barbarin, O. Mandela’s children: growing up in post-apartheid South Africa. N. Y. Routledge 2001.

Bobak, M. et al., Socioeconomic factors, percieved control and self-reported health in Russia. A cross-sectional survey. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:269–279.

Bond, P. Elite transition: from apartheid to neoliberalism in South Africa. London: Pluto 1998.

Bourdieu, P. Le capital social: notes provisoires Actes de la Rechercheen Sciences Sociales 31 (1980), 2–3.

Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital, John G. Richardson (ed), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, p. 241–158. New York: Greenwood 1985.

Brändström, A. and J. Sundin (eds), Tradition and Transition. Studies in microdemography and social change. Report no. 2 from the Demographic Database, University of Umeå 1981 (1).

Brändström, A. and L-G Tedebrand (eds), Health and Social Change. Disease, health and public care in the Sundsvall district 1750–1950. Report no. 9. The Demographic Data Base, Umeå University 1993.

Brändström, A. and L-G Tedebrand (eds), Swedish Urban Demography During Industrialisation. Report no. 10. The Demographic Data Base, Umeå University 1995.

Brändström, A. S. Edvinsson, and J. Rogers. Illegitimacy, Infant Feeding Practices and Infant Survival in Sweden 1750–1950. A Regional Analysis. Hygiea Internationalis. Vol. 3 (2002) http://www.ep.liu.se/ej/hygiea/

Cockerham, W. Health and Social Change in Russia and Eastern Europe, New York: Routledge 1999.

Cornia, G. A. and R. Paniccià (eds), The Mortality Crisis in Transitional Economies. Oxford U. Press 2000.

Dasgupta, P. and I. Sergaldin, (eds), Social Capital. A multifaceted perspective. World Bank 2000.

Durkheim, É. Le suicide. Paris: Presses universitaires de France 1991.

Field, J. and T. Schuller, (eds), Social Capital: critical perspectives (Oxford: Oxford U. Press 2000).

Gittell, R. and A. Vidal, Community organisation: building social capital as a development strategy. London: Sage Publications 1998.

Goldman, N. Marriage Selection and Mortality Patterns: Inferences and fallacies. Demography 30(2): 189–208, 1993.

Hawe, P. and A. Shiell, ‘Social capital and health promotion: a review.’ Social Science of Medicine 2000: 51:871–885.

Hertzman, C. and A. Siddiqi, Health and Rapid economic change in the late twentieth century. Social Science of Medicine 51,2000.

Hofsten, E. and Hans Lundström,. Swedish Population History. Main Trends from1750 to 1970. Stockholm: Liber 1976.

Högberg, U. Maternal mortality in Sweden. Umeå University medical dissertations. N.S. 156. Umeå University1986.

Jaffrey, Z. AIDS in South Africa: the new apartheid. London: Verso 2001.

Johansson, S. R. Welfare, Mortality and Gender. Continuity and Change in Explanations for Male/Female Mortality over Three Centuries. Continuity and Change, 6:2, 1991.

Kawachi, I. et al. The Society and Population Health Render. Vol. I Income inequality and health N Y: The New Press 1999.

Kisker, E. E. and N. Goldman, ‘Perils of Single Life and Benefits of Marriage’. Social Biology 34: 135–152, 1987.

Leon, D. & G. Walt (eds), Poverty, inequality and health. An international perspective. Oxford U. Press 200l.

Lindh, T. and B. Malmberg, Population change and growth in the Western world, 1850–1990. Working paper for SSHA Conference 2000. http://www.nek.uu.se/faculty/lindh/Recent.html

Lundh, C. The World of Hajnal Revisited. Marriage Patterns in Sweden 1650–1990. Lund Papers in Economic History 60. Lund: Department of Economic History, University of Lund 1997.

Macinco, J. and B. Starfield, The utility of social capital in research on health determinants. The Milbank Quarterly, 39:3, 200l.

Marmot, M. and R. Wilkinson, Social determinants of health, Oxford U. Press 1999.

Nelson, M. C. and J. Rogers, The Right to Die. Anti-vaccination Activity and the 1874 Smallpox Epidemic in Stockholm, Social History of Medicine, 5, 1992.

Nelson, M. C. and J. Rogers, Cleaning Up the Cities: The First Comprehensive Public Health Law in Sweden, Scandinavian Journal of History 9:2, 1994.

Nelson, M. C. Dirt, Disease and Demography. Public Health and Infant mortality in Uppsala, 1861–1895. M. C. Nelson and J. Rogers, The epidemiological transition revisited. Or what happens if we look beneath the surface? Health Transition Review 7:2, 1997.

Nordenfelt, L. On the nature of health. 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 1995.

Porter, D. Health, Civilization and the State. A history of public health from ancient to modern times, London: Routledge 1999.

Putnam, R. D. Bowling Alone. The collapse and revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster 2000).

Rotberg, R. I. (ed), Patterns of social capital: Stability and change in historical perspective. Camb. U. P. 200l.

Rothstein, B. Social Capital in the Social Democratic State. The Swedish Model and Civil Society. Politics and Society 29, 200l.

Sampson, R. J. and J. D. Morenoff, Public health and safety: community and social capital. V. Shkolnikov et al., Causes of the Russian Mortality Crisis: Evidence and Interpretations. World Development, 26, 1998.

South African Health Review, 1999–2002.

Shkolnikov, V., G. Cornia, D. L. Leon and F. Meslé, ‘Causes of the Russian Mortality Crisis: Evidence and Interpretations’. World Development, 26, 1998.

Sköld, P. The Two Faces of Smallpox. A Disease and Its Prevention in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Sweden. Report no. 12 from the Demographic Data Base. Umeå University 1996.

Studies on the social dimensions of globalization. South Africa. ILO 2001.

Sundin, J. Environmental and other factors in health improvement explaining increased survival rates in 19th century Sweden. Erik Nordberg and David Finer (eds), Society, environment and health in low-income countries. Department of International Health Care Research, Karolinska institutet, Stockholm 1990.

Sundin, J. Culture, Class and Infant Mortality During the Swedish Mortality Transition, c. 1750–1850. Social Science History, 19: 1, Spring 1995.

Sundin, J. Child Mortality and Causes of Death in a Swedish City, 1750–1860. Historical methods 1996, 29:3: 93–106.

Sundin, J. For God, State and People. Crime and Local Justice in Pre-Industrial Sweden. In: Johnson, E. and E. Monkkonen (eds), The Civilization of Crime. Violence in Town and Country since the Middle Ages. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Sundin, J. Worlds We Have Lost and Worlds We May Regain: Two Centuries of Changes in the Life Course in Sweden. The History of the Family. An International Quarterly, Vol. 4:1, 1999.

Sundin, J. Globalisation, Social Change and Health. A diachronic Perspective. Towards a Safe and Civil Society. The Contributions of Occupational and Environmental Health and Safety in History, Theory and Practise. Proceedings of ICOH Conference September 2000, Brisbane 2000.

Sundin, J. Individual Change or Environmental Reform? Historical Perspectives on Responsibility and Hygienism. In: Bourdelais, P. (ed), Les Hygiènistes. Enjeux, modèles et pratiques. Paris: Belin 2001.

Sundin, J. and S. Willner (eds.) Samhällsförendring och hälsa. Olika forskarperspektiv. Rapportserien Framtidsstudier, no 7. Stockholm 2003.

Szreter, S. Economic Growth, Disruption, Deprivation and Death: On the importance of the Politics of Public Health for Development. Population and Development Review, 23:4,1997.

Szreter, S. The state of social capital: bringing back in power, politics and history. To be published in Theory and Society, 2003.

Söderberg, J. U. Jonsson and Ch. Persson, A stagnating metropolis: the economy and demography of Stockholm, 1750–1850. Cambridge 1991.

Wilkinson, R. (ed), Why society kills. London: Routledge 1996 (1).

Wilkinson, R. Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge 1996 (2).

Willner, S. The impact of alcohol consumption on excess male mortality in early 19th and 20th century Sweden, Hygiea Internationalis, 2, 2001. http://www.liu.se/tema/inhph/journal/default.htm

Woolcock, M. Using social capital: getting the social relations right in the theory and practice of economic development Princeton 2002.