Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region

Michael 2011;8:270–294.

The Third Baltic Sea States Summit in Kolding, Denmark, in April 2000 decided to establish a Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region, with Special Representatives from each of the eleven Prime Ministers and the President of the European Commission. Its mission: to reduce, through concerted action, the risk and burden of communicable diseases in the region. Norway volunteered to chair the Task Force, and to establish a secretariat.

This report outlines the structures and the principles of the Task Force collaboration. Standardized projects were designed and implemented in six programme areas, all monitored through a common database. The Task Force also fostered wider collaboration in the areas of training in public health and health sector reforms. In all, 138 projects had either reached completion or were in progress as of spring of 2004. Direct project support amounted to ten million €, with approximately the same amount for networking, training, technical advisers, secretariat and evaluation.

HIV and tuberculosis incidence rates have either flattened out or declined at the end of this period. While the direct impact of the Task Force cannot be quantified, we can say with confidence that the Task Force heightened political awareness in the respective countries of issues related to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other communicable diseases, promoted change in national neighbourhood cooperation policies and funding, resulting in increases in national budgets to combat communicable diseases. The basis for collaboration at the political level laid by the Task Force is already bearing fruits with the setting up of Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Well-being, in which the networks created within the Task Force-framework are of importance.

The available information on the burden of communicable diseases in the Eastern part of the Baltic Sea region strongly suggests that more needs to be done to contain these epidemics. Although the rates of new cases may now be falling, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS continues to rise. The registered rates of new tuberculosis cases have stagnated, but are still unacceptably high. A wide and well-functioning network has been established, on the political level as well as the practical and professional level. These networks must be maintained, and preferably widened. The future collaboration will probably be less in the shape of project support and in terms of funding, as the economic indicators improve. Technical collaboration, common understanding, mutually supportive strategies and acting through established networks will most likely be the four pillars on which future collaboration on communicable disease control in the region will rest.

A sharp rise in the incidence of communicable diseases was observed in the 1990s in the Baltic Sea and the Barents regions, particularly in the Russian Federation and the Baltic States. Social and economic hardship had made the populations highly vulnerable and facilitated the spread of infection. HIV infections, initially among injecting drug users, and tuberculosis, in particular the multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis among inmates in overcrowded prisons, gave cause for alarm.

The Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised the issue of the threat from infectious diseases at the Ministerial Meeting of the Council of the Baltic Seas States, CBSS, in Palanga in June 1999, and at the EU Ministerial meeting on the Northern Dimension in Helsinki in November 1999. The growing concern led to a consultation in Sigtuna 31 January – 2 February 2000, at which 80 experts from the CBSS member states and the EU Commission, The World Health Organization, The World Bank, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the Open Society Institute took part.

The Third Baltic Sea States Summit in Kolding, Denmark, in April 2000 decided to establish a Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region, with Special Representatives from each of the eleven Prime Ministers and the President of the European Commission. Its mission was, through concerted action, to reduce the risk and burden of communicable diseases in the region. Norway volunteered to chair the Task Force, and to establish a secretariat. After initial consultations with relevant authorities, experts and organizations, the Task Force reached full agreement on priority areas and steps to be taken, and submitted in December 2000 a background document entitled «Healthy Neighbours» along with its recommendations. The document can be found at the website www.baltichealth.org. The Heads of Governments and the President of the European Commission decided in January 2001 to renew and extend the mandate for the Task Force for three years. The Summit in St. Petersburg on 10 June 2002 again confirmed the mandate, and issued a statement, reaffirming their concern.

Mandate

The Task Force shall:

Review the recommendations and the background documentation for concerted action in the field of communicable disease control in the region.

Develop instruments for the implementation of the recommendations.

Oversee the implementation of recommendations.

Establish and conduct an evaluation of the entire initiative.

Report to the CBSS Summit 2002 (subsequently 2004).

Prepare for the end of the Task Force and make recommendations for the continuations of activities when the mandate expires.

Members of the Task Force:

Ib Valsborg, Permanent Secretary, Denmark

Katrin Saluvere, Director General, Estonia

Ronald Haigh, Head of Unit, EU Commission

Jarkko Eskola, Director General, Finland

Reinhard Kurth, President, Germany

Haraldur Briem, State Epidemiologist, Iceland

Viktors Jaksons, Minister, 2002

Signe Velina, Deputy Director, Latvia

Eduardas Bartkevicius, Vice Minister, Lithuania

Lars Erik Flatø, 2001

Kristin Ravnanger, State Secretaries, Norway (Chair)

Andrzey Ryz, 2002

Miroslaw Manicki, Vice Ministers, 2003

Wiktor Maslowski, Adviser for the Minister of Health, Poland

Georgy M. Petrov, Vice Minister, 2001

Viktor Maleev, State Infectionist, Russia

Erik Nordenfelt, Professor, Sweden

The Task Force Special Representatives were responsible for political co-ordination and oversight of the entire initiative. The Special Representatives were also given the responsibility to ensure that agreed procedures for prioritisation and use of economic resources were followed, and to mobilise national resources and commitment during the lifetime of the initiative. One further aspect of their work was related to the enlargement of EU in May 2004, when the ‘political geography’ of the whole area changed. In this sense, the activities of the Task Force also took cognisance of the need to support accession priorities as well as to encourage collaboration with the Russian Federation, in response to the impending extension of the frontier with EU.

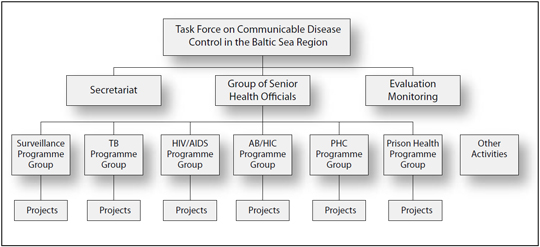

Figure1. Organizational structure of the Task Force and its units TB: Tuberculosis AB/HIC: Antibiotic resistance and hospital infection control PHC: Primary health care Other Activities: Network of public health training around the Baltic Sea, Health sector reform.

Background documents

The plan of action developed by the Task Force is described in the background document «Healthy Neighbours». This document also gives a brief overview of the health situation in the Baltic region and discusses elements of public health strategies. Finally, it sets out the scope and principles for international cooperation in combating infectious diseases .The document lists five programme areas, that were confirmed by several expert panels on project development: Surveillance; Early Warning and Vaccinations; Tuberculosis, HIV and STI (Sexually Transmitted Infections); Antibiotic Resistance and Hospital Infection Control; and Primary Health Care Services. Later, at the Summit in 2002, a further programme area on Prison Health was added.

Regarding the organizational structure of the Task Force, the Programme Groups for each of the programme areas worked as the prime engines in project development. The tasks and responsibilities of International Technical Advisers – ITAs – and a Group of Senior Health Officials – GSHO – were laid out in a subsequent document entitled «Implementation – Down to Earth», which also can be found at the website mentioned above. In 2001–02, the Task Force expanded further with the addition of working groups and advisers on training in public health and health sector reform.

Project status 0704–2004 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Approved |

Project Proposal |

Draft |

Completed |

Closed for other reasons |

Total |

||

Programme Area |

S |

1 |

0 |

2 |

8 |

14 |

25 |

TB |

20 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

31 |

|

HIV |

31 |

1 |

4 |

10 |

6 |

52 |

|

AB |

22 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

31 |

|

PHC |

23 |

2 |

4 |

12 |

5 |

46 |

|

PrHe |

32 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

38 |

|

Total |

129 |

9 |

18 |

33 |

34 |

223 |

|

It was decided to use the Logical Framework Approach, an internationally recognized tool in development project planning, as an obligatory frame for all projects. All Task Force projects were to be entered into the database and published on the Task Force website, and targets reported by the project leaders as they were reached. The website was also used by the members of the Programme Groups to draft projects. Training courses in Logical Framework Approach were given. In all, 223 projects were registered. Of these, 61 were proposals or drafts which were not finalised, or were closed. In all there were 36 projects registered for Estonia, 35 for Latvia, 45 for Lithuania, 17 for Poland and 105 for the Russian Federation.

Over time, until end of March 2004, 162 projects were posted as «approved» or «completed» by the groups. Of the 129 «approved» but not yet completed projects, there were 105 that had full or partial funding and were in progress. In addition, there were at this time 33 projects that were completed. This is a remarkable outcome, and reflects the general proactive attitude in the Task Force.

Founding |

Programme area |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

S |

TB |

HIV |

AB |

PHC |

PrHe |

Total |

|||

Not funded |

Project status |

Approved |

1 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

6 |

8 |

24 |

Projekt proposal |

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

||

Draft |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

15 |

||

Closed for other reason |

11 |

2 |

6 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

28 |

||

Total |

13 |

9 |

17 |

10 |

13 |

13 |

75 |

||

Partly funded |

Project status |

Approved |

0 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

13 |

14 |

39 |

Draft |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

||

Completed |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

||

Closed for other reason |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

||

Total |

6 |

3 |

5 |

6 |

18 |

15 |

53 |

||

Funded |

Project status |

Approved |

0 |

15 |

22 |

15 |

4 |

10 |

66 |

Projekt proposal |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

||

Closed for other reason |

6 |

3 |

8 |

0 |

11 |

0 |

28 |

||

Total |

6 |

19 |

30 |

15 |

15 |

10 |

95 |

||

Guiding principles

The Task Force set up a decentralized organizational structure, which granted very high degrees of autonomy to the Programme Groups, i.e., the panels of experts from participating countries. This approach laid considerable responsibility and authority on the project leaders. The logical framework and the reporting on the homepage, in addition to possible separate reporting to donors, were the ties intended to keep the whole initiative together.

The task of monitoring the database was outsourced to an academic institution which reported regularly to the Secretariat. These reports also formed the basis of the oversight performed by the GSHO and the Task Force authority itself. This was for many a new approach and not always readily understood. Some actors expected, even would have preferred, to work to a more traditional, hierarchical model, with a central authority directing, instructing and distributing funds from the top. But the Task Force decided early on to avoid yet another bureaucratized intergovernmental organization, and clearly wanted to reduce the potential for donor-driven projects.

Sustainability was an important guiding principle. Projects should be anchored with local authorities, who were best capable of taking local circumstances into account, and could also be expected to mobilise their parts of the budgets, in particular salaries, premises and expendables, in view of continued activities once the international collaboration came to an end.

The core elements of the collaboration thus rested on the transfer of knowledge and technology and a shared understanding of the problems, contexts and solutions. One-time investments in equipment were underwritten by external partners, and the guiding principles were flexible enough to allow exceptions, when there was an obvious need, for example to renovate premises in prisons.

Organization of work

The collaboration was based on the agreed objectives set out in the background document. Each Programme Group took these as starting points in their work to develop more specific project models, following the logical framework, in their various fields. Guidelines were then developed on how to develop concrete projects, and International Technical Advisers were placed at the disposal of initiators of new projects.

Project proposals and drafts were to be discussed, modified and finally approved by the Programme Groups. Although projects were approved, that did not necessarily entail budget approval.

A Group of Senior Health Officials, senior government officials from each country and the European Commission, were appointed by the Task Force members to oversee programme developments and project funding. The meetings of the GSHO were open to observers from WHO, UNAIDS and other organizations. The large majority of approved projects did, in the end, receive funding, either wholly or partially. Once projects were under way, project leaders were expected to report on progress through the database.

In addition to project development and implementation, many other activities were taking place. Site visits, discussions on best practices and guidelines, policy formulations, advocacy, training activities, participation in conferences and professional meetings which in par are not listed. Specifically, the participants in the Task Force and its sub-elements participated in the development of a network for training in public health, the development in pilot schemes for health sector reform, in the evaluation of the Task Force and its activities, and in laying of a foundation for an EU Northern Dimension for Public Health and Social Well-being.

Funding

It is estimated that the total cost of the Task Force is in the range of 18–20 million €in direct expenditures. This estimate only takes into account funds spent directly on projects, training, meetings and the Secretariat, including monitoring and evaluation. The direct financing, or explicitly earmarked funds for the Task Force projects as reported in the database, came in at a little short of 9 million €. There has, however, been some underreporting to the database at the time of the present writing, for which there are several causes. Either reporting has been delayed, or only partially filed, for instance, only the early instalments, or the funds have not reached the project leader at the time the records were filed. When financing goes through a Western NGO(Non-governmental organizations), the project leader often only sees part of the contribution. There are examples of cases in which more than 60 per cent of disbursed funding has been used to cover salaries, travel expenses, overheads and other expenses incurred by the NGO in question.

Denmark reports a direct contribution of 625 000 €, divided as follows: Direct project support: 322 000 €, ITA: 201 000 €, evaluation: 32 000 €, Task Force related meetings including travel expenses: 70 000 €. Finland reports a direct contribution of 1 244 776 €, divided as follows: Direct project support: 759 304 €, ITA: 420 776 €, Task Force related meetings: 64 696 €, in addition travel expenses which are not recorded. Germany reports a direct contribution of 357 800 €, divided as follows: Direct project support: 305 800 €, networking (travels, meetings): 52 000 €. Iceland reports a contribution of 361 500 €, direct project support 40 000 €, ITA and networking: 321 500 €. Norway reports a direct contribution of 8 684 000 €, divided as follows: Direct project support: 6 515 000 €, networking: 1 054 000 €, evaluation: 340 000 €, monitoring: 150 000 €, secretariat: 625 000 €. Sweden estimates its total contribution to 4 653 000 €. Direct project support: 2 075 000 €, Swedish East Europe Health Committee: 1 989 000 €, Task Force related meetings: 108 000 €, ITA: 266 000 €, networking: 215 000 €. The Unites States contributed $ 150 000 towards the cost of the ITA for HIV/AIDS.

The amounts provided by country in direct project support, as reported, are (in €):

Denmark |

322 000 |

Finland |

759 300 |

Germany |

305 800 |

Iceland |

40 000 |

Norway |

6 515 000 |

Sweden |

2 075 000 |

Sum |

10 017 100 |

There was also funding for other ongoing projects, i.e., initiatives not included under the Task Force umbrella. Examples are the Finnish Office for the Collaboration with the Nearby Areas, Swedish Eas Europe Health Committee (as mentioned), Norwegian prison health support, projects under the Nordic Council of Ministers and the Barents Health Programme, all sizeable programmes. It is not always possible to draw a sharp line between Task Force-related projects and such other, independent projects.

It is also important to note that several projects received direct or indirect support from subsidies under the EU Public Health Programme. There has been an effort, in particular by the EU Commission, to provide and share technical knowhow on EU matters within the Task Force framework, including access to EU funds such as PHARE and TACIS. A two day training course was organised in October 2001 on this issue.

Several other types of programme costs are not accounted for, such as staff costs, equipment and other expenditures for participants that have not been remunerated. The database has registered 533 names of persons making an active contribution to the work of the collaboration. These are professionals across all involved areas who have given hundreds of working hours without recompense from their usual employers to take part in Task Force projects and other activities. To put a figure on all of this work would be pure speculation.

In addition, a number of training courses and professional consultations other than those included in specific projects were organized, explicitly related to the work of the Task Force. We mention here Sigtuna 2 Conference, October 2000; the Stakeholder Conference on Training in Public Health, Trakai, October 2001; Tuberculosis among Prisoners, St. Petersburg, November 2002; Understanding the System of Epidemiology and Surveillance of Infectious Disease around the Baltic Sea, Moscow, June 2003; the Baltic Region Conference Together Against Aids, Riga, September 2003; and finally support to the Nordic-Baltic Society of Infectious Disease, in particular the Congress in Palanga, June 2004. These and other smaller conferences were funded, fully or in part, through the Task Force system. Total cost figures are not available for travel expenses and Task Force related meetings (Task Force, GSHO, Programme Groups, and Network for training and similar) because the expenditures of host countries were impossible to record. There is therefore no comprehensive statement of these costs. ITAs (including travel expenses) were funded by Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the US. Other expenditures, including the participation at CBSS meetings, contributions towards the Northern Dimension Partnership in Health and Social Well-being and efforts to promote health sector reforms, have not been fully recorded or compiled.

Main results

Originally, the Task Force, as a new health-related initiative, was given a high political priority, confirmed not least by the appointment of special, personal representatives of Heads of Governments to the Task Force group to guarantee and maintain close contact with their respective Prime Ministers.

As stated in the evaluation report, the promise of that auspicious start failed to materialize, and the Task Force Group would never attain the political influence envisioned for it. Member countries only in part displayed sufficient political commitment (in the form of funds) and not all did appoint people of political stature, empowered to make the necessary decisions (how to use funds).

If political commitment is counted only in Euros, then the results of the Task Force must be described as modest, given the magnitude of the threat posed by communicable diseases. If we look at the results in terms of the raising of political awareness of the threat of HIV/AIDS, TB and other communicable diseases in the respective countries, its incorporation on the agendas of Governmental bodies, the bilateral discussions between Prime Ministers, the changes in national neighbourhood cooperation policies and funding, and the increase in national budgets to combat communicable diseases, then we must say that the collaboration was remarkably successful. That said, translating policy changes into action takes time and since the lifetime of Task Force has been relatively short, the full impact is yet to be seen.

The Task Force laid the basis for closer collaboration at the political level, something we now see in practice with the establishment of the Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Wellbeing, in which networks created within the Task Force framework play an important part.

As to meeting the original concerns of the Sigtuna meeting, i.e., to mitigate risks and reduce the incidence of communicable diseases, the general picture is one of success. Incidence is either flattening out or declining; thanks to improved living conditions, national programmes, individual commitment and, we hope, in part, international collaboration led by the Task Force.

In summary, the Task Force has been instrumental in:

Raising political awareness of the problems related to communicable diseases.

The adoption of international guidelines in the agreed priority/programme area.

The formation of a large project portfolio in the programme areas, improved surveillance and decline in the incidence of infectious diseases.

Improving understanding of project design and management.

The establishment of a wide network of experts and health and other officials.

Cementing a basis for future collaboration in public health training.

Initiating a method to model systems that will lead to reforms in the health sector and expansion of primary health care provision.

Providing the groundwork on which the EU Northern Dimension Partnership for Public Health and Social Well-being can be developed.

Adding to the literature through the innovative design for collaboration and project development, and subsequent careful evaluation.

Specifics from Programmes

This chapter reports only selectively and briefly on each Programme. Detailed information can be found in the Programme Group reports, available at www.baltichealth.org.

Surveillance

The stated objective was to strengthen surveillance systems on infectious diseases and to verify, and if necessary amend, procedures to insure vaccination coverage.

The Programme Group consisted of State Epidemiologists who had collaborated on joint activities before the arrival of the Task Force. The group reported five meetings, the last being in May 2003, all convened as part of the regular meetings of the State Epidemiologists. The group approved twenty-three projects, two were closed, and eleven were funded and completed. (Three of these reported as closed for other reasons in Table 2.) The group did not have an ITA at their disposal.

The surveillance programme received the least funding of all programme areas. Most of the funds were spent on meetings of chief epidemiologists; exchange of knowledge and data, setting up of the early warning system «What’s New?», and the production of a «Status Report on Infectious Diseases in the Baltic Sea Region 2002». Apart from meetings, workshops and seminars, the Task Force supported the development of a database on child vaccination programmes and the procurement of computer equipment.

As a result of Task Force involvement, an early warning system was established. A database of national vaccination calendars was set up at the EpiNorth website, albeit so far without information on vaccination coverage. Biannual status reports on infectious diseases in the region will be published.

The group does not see a need for future meetings as a Programme Group. The members will meet in other connections, such as the Council of European State Epidemiologists and the North West Russian Regional Epidemiologists Meetings.

Tuberculosis

The work of the Programme Group on Tuberculosis was, at the outset, much facilitated by the work of the NO-TB Baltic initiative a few years earlier. Dr. Tone Ringdal was coordinator for this work, and became the chair of the Task Force Programme Group. She died in a car accident in June 2002. This was a great loss to the group in particular, and, of course, the Task Force. The loss of Tone Ringdal and her personal and professional contributions were much regretted.

The stated objective for this group was to reduce the burden of tuberculosis in each country to the European average (less than 20 per 100 000) and prevent the further proliferation of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

The group had an International Technical Adviser, funded by Iceland and Norway (travel expenses), at its disposal. Most of the group members saw their work as a continuation of the above mentioned NO-TB Baltic Project, which had been generously funded by the five Nordic countries (equivalent to almost 3 million € today) from 1998 to 2000.

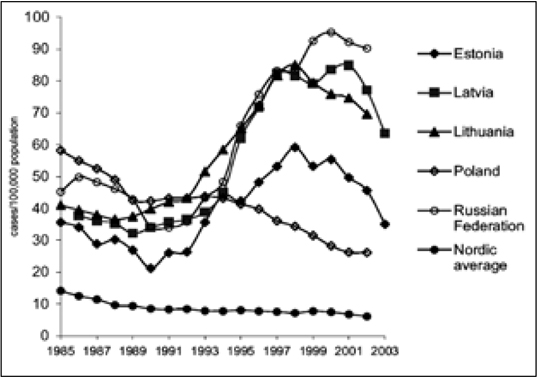

Figure 2. Tuberculosis incidence in the Eastern Baltic Sea countries per 100 000 population. Early data for Russia for 2003 give an incidence rate of 70, confirming a very positive development. Source: (WHO Europe 2004); 2003 data provided by chief epidemiologists. Note: 2003 data are provisional.

The group reports that the ideas of the Logical Framework Approach and the electronic database were received with limited enthusiasm. Many were convinced from the start that it was a waste of time and it should be up to individual project teams to plan and monitor activities as they saw fit. The group also reports that financing was a central concern. That said, all the projects were funded, raising the question of saturation and indicating that needs are met through the ongoing activities.

The group met ten times, the last being in May 2003. The group is not inclined to continue as a group beyond the lifetime of the Task Force. The group approved 26 projects, 22 of which received funding and are either already finalized or in progress. The group decided not to arrange peer reviews.

A key component was bringing the tuberculosis services in alignment with the DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short-course) programme recommended by WHO. The tuberculosis project receiving the highest funding provided by the Task Force (622 000 €), was support to the national TB programme in Lithuania. It will make DOTS available throughout the country. In Kaliningrad, projects are under way to accelerate the introduction of the DOTS programme and to improve detection of tuberculosis among HIV positive patients. Other Task Force projects aim at strengthening tuberculosis services in primary health care (Latvia, Karelia, St. Petersburg), provide social support to MDR-TB patients to increase adherence to treatment (Latvia, Archangelsk), reconstruct wards for MDR-TB patients (Archangelsk) and strengthen tuberculosis laboratories (St. Petersburg). Several projects are being implemented in the prison sector. In Latvia and Estonia, Task Force projects have improved tuberculosis control in prisons. In Murmansk, St. Petersburg and Archangelsk, prison projects are contributing to reconstruction work, the procurement of equipment and training.

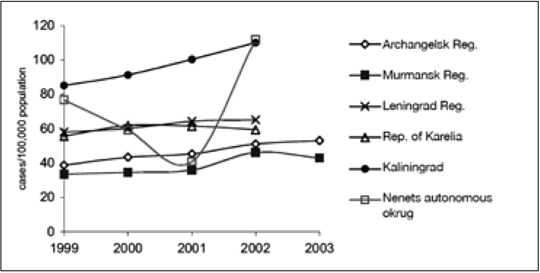

Figure 3. Tuberculosis incidence per 100 000 populations. In the Russian Federation covered by Task Force. Source: (EpiNorth 2003); 2003 data provided by chief epidemiologists. Note: Prisons and military personnel are not included; 2003 data are preliminary.

HIV

The stated objective was to prevent the spread of HIV infection, and reduce incidence to levels prevailing in the other North European states, 20 per 100 000, and, with regard to sexually transmitted infections, STIs, to Central European levels. The outputs were stated to be low-threshold support centres for HIV and STI diagnosis, treatment and prevention, clean needles, syringes and condoms easily available, an increase in awareness and knowl

edge about safer sex and universal access to treatment of pregnant HIV positive women.

The group had an International Technical Adviser, funded by the United States, Sweden and Norway (travel expenses) at its disposal. The group reports that few of the involved experts were accustomed to the Logical Framework Approach, and that because it took time before the website became functional, the tool was not used to its full potential. This issue was in part solved by inviting the International Technical Adviser to play an active role in project formulation. The report further mentions that «the rather decentralized and informal structure of contact between the group and projects, when the main idea is to give the project participants a real (sense of) ownership of their projects, leads to problems of follow up and monitoring of some projects.»

The group also reports that «we are facing a process that is growing and gradually increasing in impact. [The group] has created several international networks at different levels, starting from high-level decision-makers... to the experts at grassroots’ level. This has helped several institutions and projects, which had never before thought about being included in the international network and professional community. This soul of changes and co-operation needs to be kept.»

The group met ten times, latterly in March 2004. The group approved 43 projects, 35 of which received funding. Of these, 25 are under implementation and 10 finalized. The group conducted three peer reviews. At a regional level, several meetings and workshops were organised for medical professionals and other workers in low threshold counselling sites for injecting drug users (IDUs).

The Programme Group on HIV wishes to make two final points:

Antiretroviral treatment should be made available to all those infected with HIV.

The members of the Programme Group are expressing their willingness to continue their voluntary input provided the conditions make meaningful work feasible.

The largest ongoing HIV/STI project, in terms of funding, is in progress in Lithuania (380 000 €in external funds). It aims to improve the prevention and control of STIs by supporting centres for STI diagnosis and prevention, producing educational materials, organising STI management groups and establishing baseline data. A monitoring visit in January 2004 concluded that most of the project activities had been implemented, although preventive activities had yet to be undertaken.

Similar projects were also implemented in Latvia, Estonia and St. Petersburg. A priority area for Task Force activities has been the enhancement and support of low-threshold activities among IDUs and commercial sex workers to prevent the spread of HIV and STIs. The example of successful activities in such projects resulted in the development of the Network of outreach/counselling centres for IDUs in Latvia, established in collaboration with UNDP. In Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, St. Petersburg and Murmansk, the Task Force has supported harm-reduction programmes for IDUs and/ or commercial sex workers. In Estonia and Lithuania, Task Force projects aim to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS in the prison sector. A teaching programme in HIV care is being implemented for nurses from Leningrad oblast and St. Petersburg. In the area of STIs, in addition to the project in Lithuania mentioned above, a number of projects support centres for STI diagnosis and prevention (Estonia, St. Petersburg, Leningrad oblast, Archangelsk). In St. Petersburg, a peer support programme for youths is being carried out.

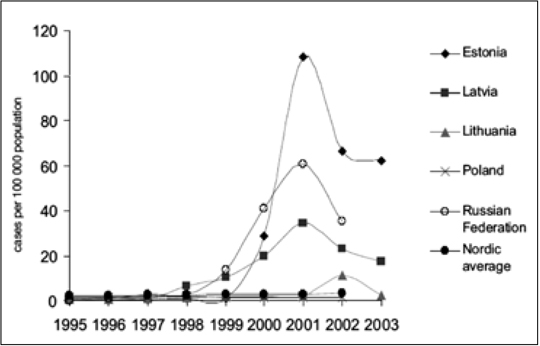

Figure 4. New HIV infections reported in the Eastern Baltic Sea countries per 100 000. Early data for Russia for 2003 give an incidence rate of 22 for Russia, confirming a positive trend. Source: (WHO Europe 2004); data for 2003 provided by chief epidemiologists. Note: Data for 2003 are preliminary.

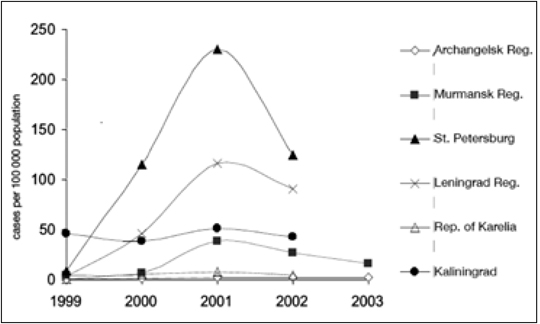

Figure 5. Registered incidence of HIV in the regions of the Russian Federation covered by the Task Force on Communicable Disease Control per 100 000. Source: (EpiNorth 2003); 2003 data provided by chief epidemiologists. Note: 2003 data preliminary; prisons and military personnel are not included.

Antimicrobial resistance

The stated immediate objectives for this group were to establish the patterns of antimicrobial resistance in the different countries; to install a set of common standards and definitions for antibiotic resistance; and to put in place hospital infection control procedures and arrangements in all hospitals in the region.

Also this group reports initial difficulty with the LFA. «Although it was thought that all project participants should be able to use the database as a means of project progress tool, it was the ITA who entered most of the data of the projects into the database. This was done during… the year 2001 and continued in 2002. Later, some of the project leaders hesitantly learned their way through the database jungle and did work with the database, i.e. writing additions to the projects etc.»

The Programme Group established a set of project planning and management guidelines:

Relevance – proposals shall be relevant to antibiotic surveillance, antibiotic consumption and hospital infection control.

Project leader – the proposal shall designate a relevant contact person to head the project.

Established network – the project shall preferably be based upon an established network within the country or the region.

Sustainability – the programme shall be sustainable after the project period.

Political commitment – the project shall be supported by the governments of the countries involved.

Budget – the proposal shall contain a detailed and relevant budget for the project period.

Globalisation – the project shall generate results of relevance to sectors other than that within which the project takes place.

It was agreed that the Programme Group should function as a project review committee and in conjunction approve projects according to the above principles.

On a positive note, the report concludes that «The collaboration among programme groups was founded on the ability of the secretariat to keep the information level high, and on the collaboration among ITAs, which appeared to function very well. In this respect, the quality of the Task Force website was extremely high. Also, the input and string pulling of the secretaries from the Secretariat was excellent.» The group also suggests that a longer preparatory phase with time to acclimatize to the whole Task Force concept for the participants of the programme groups would have been advisable. The group had an International Technical Adviser, funded by Denmark, at its disposal. The group met eleven times, the last in March 2004. It approved 25 projects, 21 of which received funding. All of these latter projects are under implementation. The group conducted no peer reviews.

The establishment and strengthening of surveillance systems of antimicrobial resistance was one of the key purposes of the Task Force projects. Laboratory capacity has been enhanced in Archangelsk, Latvia and Lithuania. On a regional level, laboratory staff have received training and a project for the establishment of a template for education in infection control, consisting of material for distance learning, a format for workshops and postgraduate courses, has been set up. Further training workshops were organised in Latvia, Lithuania and St. Petersburg. There have also been regional workshops on standardising methods of testing for antimicrobial resistance. Task Force projects on antimicrobial resistance laid the groundwork and formed an incentive to develop a National Antibiotic Resistance Control Programme in Latvia. The Programme is based on the EU principles in this area. Two hospitals in Estonia received Task Force support for reconstruction and infection control equipment. A major constraint in assessing the effectiveness of these activities is the lack of baseline data. Consequently, several prevalence studies have been initiated, inter alia in Estonia, Lithuania, Murmansk and Poland. However, so far no such information has been posted on the website of the Task Force project database. It will be necessary to wait for these data in order to evaluate progress in reducing the number of hospital-acquired infections.

Primary Health Care

The report of Programme Group on Primary Health Care is available at the homepage of the Task Force. The group is planning to issue a revised printed report in June 2004. The stated objective for this group was to foster commitment and build competence in the primary health care sector in the region with regard to prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. The group had an International Technical Adviser, funded by Finland, at its disposal. The report discusses funding for projects, and regrets both shortages and lack of earmarked funds, as they would have preferred to combine the approval of projects with a decision to provide funding. Project applications had to relate to different donors and organizations using different applications (and reporting) standards. This group had fewer problems with the logical framework than the others, concluding that «to guarantee comprehensive planning and sustainability, individual projects should be constructed according to the Logical Framework Approach. Learning this takes time.» The report adds that the development of primary health care must be a basis for health care reforms. Primary health care should be developed on a broader basis than communicable diseases alone. The group encourages collaboration around the Baltic Sea region in the future as well, including the continuation and replication of existing projects. The group reports that the Nordic countries «have been able to run stable primary health care… Over the last 15 years, the Baltic countries, Poland and Russia have made significant changes to their health care systems and have declared family medicine the cornerstone of their changed policies. The expected overall trend in primary health care development is positive and there is a continuous development in the main target area of the Task Force.»

The group met 18 times, the last being in May 2004. It approved 40 projects, 33 of which were funded and implemented, of these 12 are listed as completed. The group conducted peer reviews of two projects.

One of the main objectives of the Task Force projects has been to improve primary health care. In Russia, projects have aimed to develop continuous medical education for family physicians in North West Russia, to establish a manual for training in family medicine, and to improve the quality of services by developing and agreeing on clinical guidelines. Projects in Archangelsk and Karelia aim at the implementation of models of primary health care. There are also several projects strengthening reproductive health services. In Russia, a project supports the development of clinical guidelines for primary health care doctors in the area of women’s health. A survey on reproductive health problems is being implemented in St. Petersburg, Estonia and Finland.

In the document «Healthy Neighbours», the Task Force acknowledged that it would be difficult to evaluate the impact of its intervention in the area of primary health care. Despite this reservation, one of its stated goals was to get 400 people through one first cycle of training or exchange within a year. Although exact numbers are not always given in the project database, capacity building and the training of primary health care workers have indeed been the main activities of the Task Force in this programme area. Such work was also aimed at general practitioners, nurses, primary health care workers, administrators and health promotion volunteers. In Russia and the Baltic states, curricula and distance learning programmes on control of communicable diseases are being developed.

Prisons

At the 4th Baltic Sea States Summit in St Petersburg, in June 2002, the Heads of Governments stated that health in prisons required urgent attention due to the risk of the spread of communicable diseases in these institutions. It was decided that a new program group should be formed under the Task Force.

The Prison Health Programme Group had an International Technical Adviser, funded by Sweden, at its disposal since late 2003 only. The group met seven times, the last in June 2004. The group approved 34 projects, 24 of which received funding, and all of these are under implementation. The group conducted no peer reviews. The group was, as mentioned, established in January 2003, much later than the first five programme groups. This explains why we find a certain level of thematic overlap between projects of the first five programme groups, some of which prison based, and the project presented to the Prison Health Programme Group. Prison projects run by the first five groups have nevertheless remained the responsibility of their respective Programme Group and not been transferred to the prison group. Of the projects that secured funding, most Task Force resources in this programme area were spent on improving hygiene in prisons (Archangelsk, Karelia, Leningrad region, St. Petersburg). In 2002–03, the Task Force worked alongside the WHO Prison Health Programme and the Prison Health Studies, King’s College, London. In addition to the two major conferences on Prison Health and Tuberculosis in Prisons mentioned earlier, there was a meeting of prison chiefs and tuberculosis doctors from St. Petersburg, Leningrad and Karelia in Helsinki in September 2003; and there are ongoing training programmes for prison staff and prisoners in Estonia, Latvia and St. Petersburg.

Network for training

The Task Force organized a Stakeholder Conference on regional collaboration in training in public health, 17 October 2001, in Trakai, Lithuania. The conference was attended by 80 representatives from health authorities, academic institutions and practitioners from various fields of public health, predominantly communicable disease control. A working group was set up in consequence, which in 2003 issued recommendations to the Task Force to establish a network of collaborating faculties and institutions. On 5 May 2003 the Task Force endorsed the document from the Working Group and asked the group to become an Interim Council of the Public Health Training Network. This Interim Council met four times in 2003 and a Permanent Council was formally constituted in February 2004 upon appointments of members by the respective Ministries of Health. A secretariat was established in September 2003 in Estonia to steer common tasks of curriculum design, course development, training and recognition of exams. One of the first tasks of the Permanent Council was to seek funding from regional and European institutions, to which end a comprehensive application was submitted to the EU Public Health Programme 2003–08. The steps that follow involve curricula design, defining levels of competence, exam rights and exchange of teachers.

Health sector reform

The fragmented world of health service is a constant problem in every country. The need to achieve higher standards more efficiently through a better balance of resources between the different elements in the treatment line and better internal communication is well established. The Task Force was challenged to address this issue of health sector reform. It was decided not to try to start health sector reforms in a big way, but to run five pilot projects in geographic areas where balancing interrelated systems should have the focus. Changing institutionalized systems requires hard work and lots of time; it will take years, for instance, before people working on the pilot projects have sufficient experience to engender change in the bigger setting. The projects in the process of being formalized are in Archangelsk and Karelia in Russia, Poznan in Poland, Finnmark in Norway and Siauliai in Lithuania.

The idea is that each project should meet local needs and be operated and governed by local governments and project organizations. At the same time, efforts are being made to bring the pilot projects loosely together and to learn from each other. An expert advisory group is being formed.

EU Northern Dimension Partnership in Health and Social Well-being

The Task Force was given a mandate for four years. As documented in this report, a broad range of activities were initiated and carried through. But clearly, the problems of communicable diseases have not and cannot be eliminated. Continuous trans-border collaboration is desirable and should become a permanent feature.

The EU Northern Dimension is an initiative the aim of which is to strengthen regional collaboration. The second Plan of Action covers 2004

– 06, and includes public health. On a Finnish initiative, and after painstaking preparations in 2003, a Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Well-being was established in Oslo, 27 October 2003. In addition to issues related to communicable diseases, the Partnership will address concerns such as life-style-related non-communicable diseases, and social determinants of public health problems and diseases. The objective is to establish an over-arching structure that brings all partners to the same table at the Partnership Annual Conference. Sweden is in the chair for the first period, and a secretariat is being established at the premises of the CBSS secretariat in Stockholm.

It is foreseen that a large part of Task Force structures can be taken further under the Partnership. This seems clear for the Council of the Baltic Sea Public Health Training Network, the work on health sector reform and for the Task Force database, which will be adapted to the needs of the Partnership.

There will be a year of transition in 2004. It is suggested that the GSHO should continue to function during the autumn, to oversee the smooth transfer of responsibilities for relevant Programme Groups, and support the development of health sector reform initiatives.

Conclusions

The Task Force was established in response to grave concerns regarding the proliferation of communicable diseases in the region.

The high-level initiative and support made it possible for expert groups to come together to devise and implement projects with little delay.

The Task Force did mobilize funds for collaboration and project support. The total sum was modest, given the magnitude of the threat posed by communicable diseases.

The decentralized, equal-partner organizational approach put in place by the Task Force, along with the database set up to enable oversight and ease communication were not followed with adequate information and training

During the mandated lifetime of the Task Force, the situation with regard to communicable diseases improved. How much of this improvement is due to Task Force intervention can not be measured, but is likely to have been significant.

The Task Force collaboration had many other beneficial consequences over and above the lowering of disease incidence rates, most importantly the harmonization of views on public health practices and establishment of a wide network of personal and professional cross-border contacts.

Evaluation

The Task Force was evaluated under the oversight of a Steering Committee, with members from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Moscow Medical Academy (Sechenov) and Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Oslo. The evaluation team looked at three areas, the political context, the programmes and selected projects. The use of the database, and the monitoring of the database was a forth element.

There are five evaluation reports available. One of the studies, Health as International Politics by Geir Hønnesland and Lars Rowe of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, was recently published by Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Two complementing programme evaluation reports, from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Russian Central Research Institute for Public Health Research, and a report on monitoring, including a database user survey from the University of Oslo, are available at the homepage. There are also reports from five of the Programme Groups and peer reviews. A fifth, summarizing evaluation report, issued by the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Oslo, is forwarded by the Steering Committee to the Summit.

Recommendations to the Summit of the Prime Ministers in the Baltic Sea Region, 21 June 2004

The Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region completed its mandate at the 5th Summit of the Baltic Sea States in June 2004.

The GSHO and the Secretariat is asked to continue its work to the end of 2004 with a view to assisting and overseeing the transition of database, networks and relevant programmes to the EUND Partnership on Public Health and Social Well-being, and to oversee the completion of projects

The Prime Ministers and the President of the CEC recognize the pioneering role of the Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region in tackling the major health problems created by HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, and stress the need to ensure that the work continues under the Partnership in collaboration with other relevant actors such as the new European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the World Health Organization.

Epilogue

The available information on the burden of communicable diseases in the Eastern part of the Baltic Sea region strongly suggests that more needs to be done to contain these epidemics. Although the rates of new cases may now be falling, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS continues to rise. The registered rates of new tuberculosis cases have stagnated, but are still unacceptably high.

A wide and well-functioning network has been established, at the political as well as the practical and professional levels. These networks must be maintained, and preferably widened. However, future collaboration will probably require less project support and funding, as the economic indicators improve. Technical collaboration, common understanding and mutually supportive strategies, and acting through established networks, will probably be core elements of future collaboration on communicable disease control in the region.

Norwegian Directorate of Health

P.O.Box 7000 St. Olavs plass

N-0130 Oslo

Norway

harald.siem@helsedir.no

1) Revised version of the final report to the 5th Baltic Sea States Summit, Laulasmaa, 21 June 2004.