The food market metaphor

The majority of cities have food markets; places to buy necessities for the day, where regular shops are mixed up with producers coming in from the countryside or the harbour, offering their harvests of the season or their catch of the day. However, to say that the Central Market in Riga, the Rigas centraltirgus is definitely one of the larger of its kind, is a clear understatement.

Hangars without zeppelins

The five halls behind the main railway station in Riga are architectonic monuments pointing to technical and social change by themselves. They look like zeppelin hangars – which they were, in fact, designed for. However, the hangar metal constructions were bought by the Riga municipality and erected as market halls 1924–1930* See http://www.architektura.lv/do_co_mo-mo/ob_3.htm ( 041004). The period between the two world wars when zeppelins silently cruised the skies and were perceived to have a future in commercial transportation, was short and already waning. These prestigious looking structures probably have to be regarded as a sign of the proud Latvian nation building process during the inter-war years of independence: but like the era of the zeppelins, the era of independence faded out.

Today the zeppelin halls are crowded with thousands of people. The space outside and inside was filled with vendors and customers in the early nineties when I came here for the first time, and it is also full in 2004 and 2005. There have been gradual changes; when I compare my old photographs from the time before the «no photography» sign (for some unknown reason) came up, with what I see today, I realize that one world has been converted into another. Strolling through the market halls at frequent intervals over the years, in fact, has been to take the temperature on the development in Latvia as a whole, converting the food market to me into a cultural metaphor.

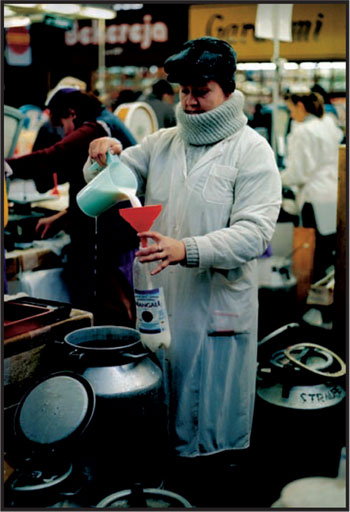

The Riga food market serves a large part of the city population. But while people in 2004 walk around more or less like in an oversized supermarket, they earlier behaved more Soviet style, lining up and patiently waiting for their turn at the counter. I still have some scenes on my retina; the milk lady pouring into the bottles and jugs brought by patiently lined up customers, while cats were waiting even as patiently for milk to spill over.

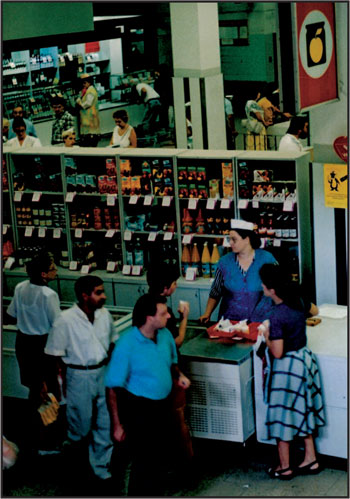

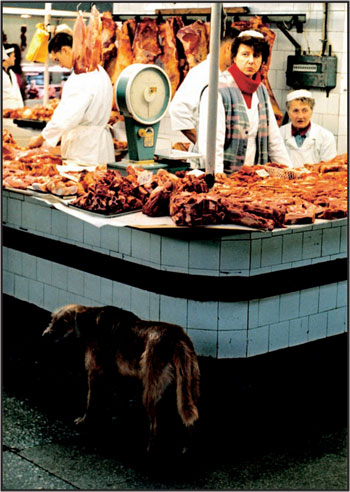

Sales desk in one of the Riga markets halls in 1993.

Buying of dairy products in 1993.

The daily bread

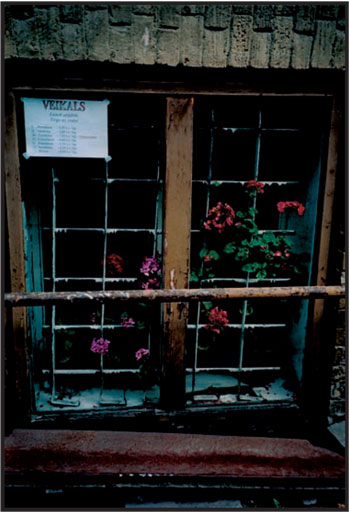

An alternative to the central market was to visit the ordinary shops. The store on the corner of Elizabetes iela (in Soviet times Kirova iela) and Antonijas iela (in the Russian period Paegles iela) could provide you with the goods they had, but you would probably need to go elsewhere too; unless the mini-market of street-sellers on the sidewalk outside the shop could offer the remainder of what you wanted. Filling your bag could be time consuming.

Or you could show really urban behaviour and approach the mega store of the time, the «Universalveikals» in the Valnu iela (Wall street in the Old city, also the same name before, then only also spelled with Cyrillic letters). An unaccustomed Western visitor in the early nineties would probably feel a little strange inside the grey building with its many floors. In the different departments with its sparsely filled shelves you had to do your shopping as people had done for decades in Soviet cities. You first presented your wish at the counter, pointed out the item demanded if it was there, got a buying order filled in at the desk, forwarded it at the cashier where you had to pay; then you had to return to the desk of purchase, where your package would be prepared upon receipt of the proof of payment from the cashier. By the time you got back on the street and you had got your goods in your hands, at least three or four persons had assisted you in your venture.

But the «Universalveikals» was really universal. There were different departments upstairs, to be approached by means of the posh parquet covered staircase, heavily worn through decades of busy feet. At the beginning of the 1990s, however, the traffic was seldom that overwhelming, not because Latvians did not have need for supplies, but because more attractive, although more expensive, Western merchandise was available elsewhere. A Russian «Lomo» camera from the photographic department of «Universalveikals» had not the same social appeal as the Nikons seen around photographers’ necks on Discovery Channel.

Not only was shopping at the Central Market swifter than in the shops, the prices were also lower. Even though the food market concentrated on food, most other sorts of wares could be obtained from the selling stalls outside, new and used, from Western music-cassettes to plastic bags with names of prestigious shops in London and Paris.

Shopping changes

I did not recognise an important sign of change myself, but I was told: Do you notice that now we have fresh vegetables all the year round? As late as twenty years ago, many more of the products offered were season-dependent.

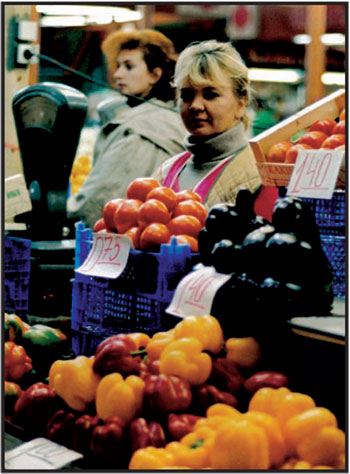

Riga market fruit seller (1997).

Selling milk (1997).

Riga «Universalveikals» 1993: A scent of a modern department store, but still old-fashioned.

These days, new and continuous imports made choices predictable. The basis was laid for a much more durable and consistent nutrition on the individual level, but on the other hand, the thrill by obtaining the first apples of the year was lost.

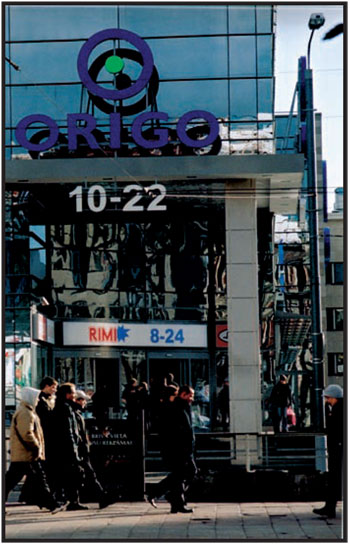

During the 1990s foreign investments proliferated in Latvia. As a relic from the Soviets, also «Universalveikals» fell victim to capitalism and liberal market forces. An example: To the right on the ground floor, where you previously might buy your bottle of Riga black balsam (traditional bitter liquor) through a cumbersome procedure, the interior was thrown out and the Norwegian food chain RIMI moved in with a supermarket designed as a blueprint of all RIMIs elsewhere, with self service trolleys and overfilled shelves. The sentiments towards this and other signs of market imperialism were sometimes ambivalent among the Latvians, but one effect should not be underestimated – the effect on quality. Admittedly, the supplies in RIMI and other branches of Western chains often belonged to the upmarket price bracket, but the population, at the same time experiencing a slowly increasing life standard and buying capacity, appreciated the higher quality – a challenge to the traditional shops and to the Riga Central Market as well. Since this period, RIMI and other chains have proliferated in Latvia.

The Riga Central Market is a metaphor of Latvian development because of the rapid changes taking place inside the hangars. When I was accompanying my medical students around, pointing out to them important issues for their study of nutritional hygiene, we sometimes brought photocopies with us of the standard Norwegian textbook from 1958* Natvig 1958.. There was a lag of forty years; the book, long outdated in Norway, here was just the appropriate orientation tool. However, this observation must not be superficially interpreted as a sign of lack of knowledge or resources in Latvia, the bearings are wider: If you pass a certain level of food safety, further developments in the field of hygiene will often reflect priorities; which investments you choose to take in competition with other possibilities in other areas. If the main priority is only the provision of hygienically acceptable foods, the situation is different from if you also have to compete with other issues, such as on quality, modes of display, alternative choices etc. There will gradually be an increasing willingness to pay also for such values in a society undergoing a transition in living standard, and difficulties may arise

Almost on the footstep of Riga Central Market lies the Riga branch of the Finnish Stockmann’s department store, opened 2003. It is obvious that its polished marble merchandise presentation accelerates the contrast, not only to the Riga Central Market, but also makes the rebuilt «Universalveikals», although now with escalators and international style, look rather dull. And the same effect is displayed by the supermarkets and hypermarkets alongside the Daugava banks or along the main roads leading to the city centre. Sometimes price policies in the chains even offer special sales which really threaten the central market’s ability to compete on price.

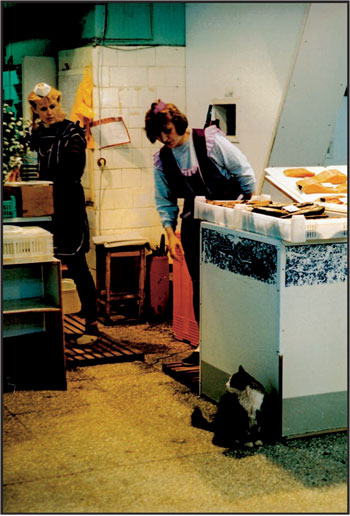

Cat in Riga Central Market fish department in 1998: On duty chasing rats and mice, or simply sneaking for fish?

Riga Central Market dog in 1997: Definitely out for food!

Hygiene in transition

The student excursions to the Riga Food Market gave opportunities for interesting discussions in the group: What is really necessary on the hygiene front to maintain the health of the population? What is the minimum? In modern societies there are important aspects of the concept of hygiene which have attracted less attention than they deserve: the cultural sides and overtones. In a military camp it is possible to have basic hygienic regulations which are fully sufficient to prevent the spread of disease, but they do not necessary comply with, say, aesthetic values. Discussions of hygiene measures today are often blurred because hard fact basics and normative preferences are mixed up. In addition, hygiene requirements are highly context dependent. That which is sufficient on a lonely farm is usually far from acceptable in a crowded city. Therefore, what you observe as hygiene standards will be a result of a series of factors, many of them cultural. Riga Central Market demonstrates this point in the field of food hygiene.

Another field where corresponding considerations apply is that of sanitation standards, where also anyone can observe that changes have occurred in Latvia during the last decades.

The nearly endless crowds of customers at the Riga Central Market also brought an important issue into the discussion with the students. Examples: How is the connection between the time the food stays in the market halls, and the hygiene measures required? It is obvious that if the time between production and consumption is short, risks following deleterious microbial contamination are less serious than if the food is displayed and stored for days. In addition, what is the connection between hygiene on the one hand and traditions and habits in the preparation of foods on the other? If thorough frying or cooking is normal practice, the situation is less critical than for those preferring sushi, beef tartar or rare steaks.

In the early nineties produce was normally displayed on tile covered benches and counters only. No refrigeration was seen. On chilly winter days, when temperature inside of the halls was rather low, this might be acceptable, but what about summer? Barriers between customers and produce were rarely present, and trolleys with meat were, and still are, brought around without any coverage. A series of principles from the field of nutritional hygiene could be discussed, and the Riga Central Market was the showpiece, an exhibition of Norwegian past.

Milk was frequently sold from open cans, and cheese products were offered from open trays. Consideration about spread of tuberculosis through milk and milk products lay at hand. This was important, not least because tuberculosis, also with treatment resistant bacteria strains, today seems to be a re-emerging problem.

There apparently was a system of hygiene control. A lady behind a meat counter told us: «They come here and place a red stamp on the hams». But by whom and on what criteria was approval given? My co-author Guntis Kilkuts tried to find out some years ago. He eagerly phoned around, but the people in charge were always in meetings, on vacation or simply not there. At last he perceived the obvious message given – do not ask. For a while, parts of the food marketing business allegedly had some mafia ties, making it unhealthy to inquire too much about food control and the like.

Market and modernisation

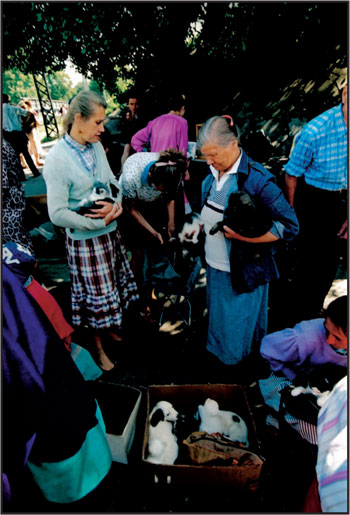

Then something happened – on the business side cash machines popped up, on the hygiene side refrigerators where introduced all over the 16 000 square metres sales area. Glass shielded counters protected the food display. The ladies selling kittens and puppies under the railway bridge outside disappeared. The Riga Central Market changed from being well suited as a teaching tool for Norwegian medical students; after all, what they can learn now, could easily be taught in any supermarket at home in Norway – apart from the experience of the impressive dimensions.

There are other changes too. A new first floor has been put in some places, expanding the sales area, and the component of non-food merchandise is larger. This may be a sign of the effect of liberal market forces on food stores, also observed elsewhere. When competence tightens in the food spectrum, non-food items may attract customers and render a better all over income potential.

But still carp, unaware of animal protectionists, are splashing nearly suffocated around in basins waiting for the customer’s frying pan, and still pure pork fat can be bought as a special delicacy, despite what nutritional experts might claim about fat intake and future health.

Pets for sale outside Riga Central Market in 1993.

Customers as a collective

Looking at all the people mingling around in the Riga Central Market, buying or only «window shopping», may spark more general reflections. In the first years after the exit from the Soviet Union the crowd still looked very homogenous. Clothing used to be in subdued colours, a bluish grey often preferred. Fur lined winter caps of the same colour topped many male heads. Scarves or clothes were used instead of hats by females, the young and elderly. Now variation is substantial, reflecting both personal taste and access to the offers from the international market.

Ten years of change in consumerism:

Local Latvian shop 1993,

and all-day shopping 2003.

However, still there is a sort of homogeneity which makes a difference as compared to, say, a crowd in Oslo. People with another skin colour, which in Oslo almost go unnoticed, because they are so many and because we are so used to immigrants, are still relatively rare in Latvia. The ethnic issue of Latvia comes up when you use your ears You can bet that the little lady selling second hand goods in the short corridor between the hangar halls speaks Russian, like her fellow babushkas at the entrance. And listening to the small-talk of the customers in all of the halls will convince you that here are many ethnic Russians around. But there are ethnic differences on all levels. Watch the dark suited, sun-glassed men accompanying long-legged blondes from blacked out Mercedes into the cool fashion boutiques.

The ethnicity issue

Even if you do not notice it at the first glance, using only your eyes, the ethnic division problem in Latvia is substantial* See e.g. Steen 1997 and Hewitt 2002.. But the issue is not as obvious as in other countries where ethnic differences are connected with people looking different. You see whom you are different from. Walking around in this peaceful crowd which a short time ago underwent major societal changes which impacted every part of life, and even the way of thinking in the minds of everyone who was old enough to perceive the events of 1991, you wonder: Was it just by chance that the disastrous consequences of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in, say, Chechnya were not repeated here?

In 1993 33,4 % of the Latvian population were ethnic Russians, to which number must be added 3,2 % Ukrainians and 4,2 % from Belarus. Apart from a small number of Poles and others, this means that just 54,0 % were indigenous Latvians* Steen 1997.. And to this large group which potentially could be alienated by nationalist Latvian hard-liners, there also are great numbers ethnic Latvians who had worked for the Russians, or had been employed by the Soviet authorities or had other contacts with the former regime.

However, one has to remember that Soviet rule was a whole and comprehensive system of itself* Hendel 1963, Fainsod 1967.. On the one hand it gave ideological legitimacy to those who later could be accused of collaboration, when the Russians became regarded as occupants. On the other hand it also founded a philosophical state in the population to which the principles of Western democracy seemed strange. Later on it became a sort of virtue to think in terms of economic liberalism. If this formerly was considered at all by the average citizen, it was thought of with disgust.

One could have feared that the apparently homogenous stream of people walking between the counters in the food market and leaving by the crowded bridge into the street of January 13, 13. Janvara iela, could easily have been on the brink of a civil war. But such atrocities never came.

We have already mentioned that the prospects of a more rapid growth in living standards for Russians in Latvia than in Russia probably acted as oil on the waves. In comparison with other former Soviet republics, religion did not play any significant role. Blood was not shed here for the sake of belief. Although church life has flourished since the ties to the East were loosened, supposedly nobody would sacrifice their life because of religion in a country which officially had pursued an atheist line for fifty years. In addition, the children growing up into new generations of citizens had been educated in a down-to-earth public atmosphere without any religion competing with communist ideology. The revival of religious life to a significant degree has probably to be regarded as part of joining an outside culture; being only weak as a political factor. This phenomenon is in contrast to that which can be observed in countries with, for example, strong Moslem communities opposing Christians, or in traditional Christian countries where religious affiliation to the Catholic or the Lutheran church also implies social class differences.

In the chapter «National identity and the democratic integration of Latvian society» in the 1997 anthology by Steen, integration issues are covered in depth. Here, Michael Rodin claims that there is no evidence for ethno-cultural conflict between the ethnic majority and the Russian and other ethnic minorities, and strong evidence points to the existence of two principal cultural communities and identities among Latvians and non-Latvians. Reviewing the transition from the totalitarian Soviet-style integration of ethnic groups like the Latvians and their country Latvia into an indivisible empire, to a modern democracy with identity of its own, Rodin concludes that there is no room for open conflicts as both parties have shared interests in creating a common political identity with tolerance for cultural differences.

However, this does not preclude hard times, e.g. in the question about how to deal with activities in the past on the individual level, people who had been loyal to the Russians and taken up actions which then perhaps were legitimate, but now are regarded as both illegal and as treason. The separation of wishes for law and order on the one side and for revenge on the other implies balancing on a sharp edge. Hewitt* Hewitt 2002. has covered this topic and put his observations into a useful theoretical framework. Readers, who are old enough to have memories of the similar process going on in the former Germanoccupied countries after the Second World War, will recall the same conflicts and dilemmas.

In Latvia, some principally important law suits were carried through after the liberation. A proof that «liberation» for the time being is a often heard word, can be found in one of the museums of central Riga: The occupation museum, a centrally placed ugly black coffin-like building, close to the rebuilt city hall, established in 1993 to maintain the memories of atrocities from the Soviet time, now also covers the German fascist occupation.

When Soviet rule was over, prosecution was instigated for political activity, for individuals including Alfreds Rubiks, a former chairman of the Latvian communist party who had supported the August 1991 coup attempt. In 1995 he was convicted to five years in prison. Participation in military activity was also on trial. What about those troops who supported Moscow during the turmoil around 1990, and who could defend themselves by claiming that they were following orders?

The delineation between political, military and criminal activities was also illuminated in the court room. Alfons Noviks, the mighty local NKVD-leader in Latvia, i.e. the head of the Ministry for Domestic Affairs, was prosecuted for deportation and execution of 60 000 Latvians in the 1940’ies and early 50’ies and got a life long sentence in 1996.

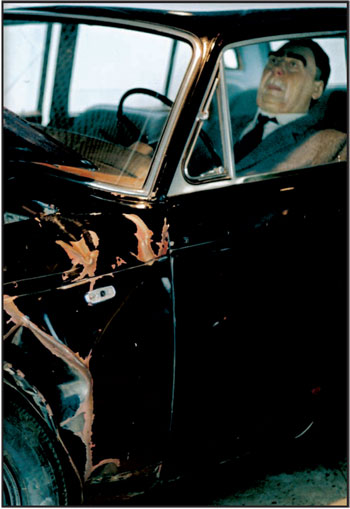

The paradox of legitimacy perhaps most clearly came to sight in the case of Vasiliy Kononov, a guerrilla commander of World War II who had raided a village during the war, killing fascists and traitors and receiving a Soviet military medal for his deed. When secret archives were opened and the cultural background had shifted, the former Soviet hero was arrested in 1998 and accused of war crime. In 2000 77-year-old Kononov met his destiny and was convicted to six years in jail.

Perhaps of more personal interest to the general public was to which degree cooperation with former authorities should disqualify for positions in the new society. In this field there always have been difficulties in countries liberated from occupants or getting new regimes in other ways. In the case of Latvia, the expertise held by people who had, under the prevailing circumstances, worked in the legal Soviet administration, was also needed by the new Latvia.

The social and economic transformation of Latvia is easy to see. Less visible is the cultural transformation which is related to the language situation. In 2005, it is 14 years since Latvia was part of the Soviet Union. Already now there are many children who do not understand Russian, and in a couple of decades there probably will be a substantial proportion of the population to whom Russian is a foreign language as is the cultural setting to which it belongs. However, as the Russian part of the population will prevail, the language question may create stronger division lines in future.

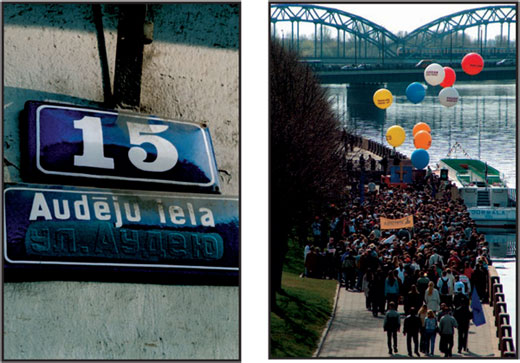

The upper left picture from 1993 shows how the language problem had been solved with paint on a street sign. The upper right picture shows that language was an issue on the EU admission day of May 1, 2004: Along with the celebrations, Russians demonstrated in favour of Russian in schools.

All over former Soviet Eastern Europe such topics have been issues for discussion, and different solutions have been chosen. In Latvia requirements to be fulfilled for attainment of citizenship were part of this, a problem faced by many ethnic Russians. Hewitt suggests that the ethnicity and citizenship issues dominated the public political agenda to such an extent that the judicial clearing of the past lost interest as compared to other societies. However, it remains to be seen if an informal rejection of Soviet collaboration will prevail even after the last law suit case has been closed.

A doll of Leonid Brezhnev in his crashed Rolls Royce, viciously displayed in the Motor Museum of Riga 1993.

When comparing the processes in Latvia with the situation in countries which had been under Nazi occupation under The Second World War, it should be remembered that in such societies persons taken to court or repressed in other ways, were often indigenous people defined by membership of certain political parties or organisations. Alternatively, these individuals might have assisted the occupant in activities directed against their own country. The occupying country itself was not part of this. In the case of the countries of the former Soviet union, the Russians (especially in Latvia where they were such a large part of the total population) had a double role of occupying force and regular inhabitants – a fact which in itself precluded any large scale purge.

The situation of the minority Russians has also been subject to in depth research. As an example, in her 1996 thesis, the Norwegian social anthropologist Torunn Hasler* Hasler 1996. published a field study from Latvia where her Russian study subjects told about their perception of the situation. Among her conclusions was that the Latvian build-up of a new nation led to a disintegration of the Soviet structures which the Russians were part of and accustomed to. Traditional networking conditions were reduced, at the same time as the new situation offered new possibilities. But she stresses the fact that Russians in no way felt themselves as intruders, because they had been sent to Latvia as part of a needed workforce, or as employees and members of a community not defined by geography, for example the Soviet railway system or other of the pan-Soviet societal structures. Hence the title of her paper, which translates as: «Here is my home».

It is obvious that the apparently homogenous crowd in the market halls is far from homogenous, even if the people around might look so. They are not multicultural, as an urban crowd might be Oslo, Stockholm or London. They represent two cultures living side by side: A Latvian identity under construction and a modified Russian culture under establishment.

In a health perspective this ethnic dualism could be studied in light of the well established health promoting health factors – social investments, social cohesion and social networking possibilities.

Social investments were failing after 1991 for both groups. Supportive systems like caring for the sick, provision of work etc. could be taken for granted under Soviet rule, even if faults and low standards were common, a situation quite different from the liberal market philosophy and its demand for competition and personal efforts. Rigidity and lack of personal freedom of choices were sacrifices to be made, willingly or not. It remains to be seen if the new social investments will be evenly distributed and beneficial to both of the main ethnic groups.

The social cohesion under the new circumstances, i.e. family structures, friendships, stability in relationship and living conditions should be studied and compared for both groups, and so should the third factor, the possibilities for voluntary setup and participation in stable personal networks.

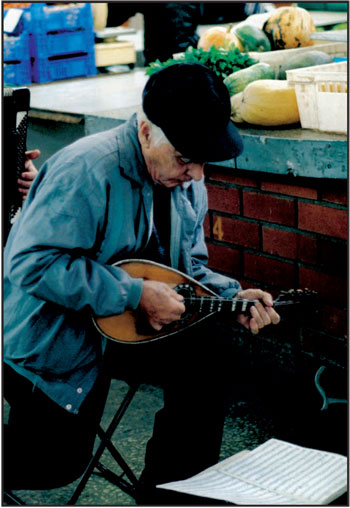

String player in the Riga Central Market 1997.

Bread, sprats and traditions

About to leave the Riga Central Market I always let myself be guided by the smell of bread; Latvian black bread. A juicy and slightly sour fragrance provokes the taste buds from a distance. In one of the halls the supply is ample: Rudzu maize, Saldskaba maize etc. Am I correct in thinking that over time these traditional sort of bread will have to yield to Western tasteless fluffy wheat brands, which are depending on cheese or sausage to give a really good taste, instead of doing so just by itself? Do I observe that traditional, well tasting and above all cheap nutrients are sacrificed on the altar of increasing living standards?

Luckily, the food market is great, the counters abundant and the exit of oldfashioned products in the near future not that likely.

There are also boxes of traditional Latvian sprats available, cheap and tasty. I buy some bread and some cans before I leave.

Latvian bread and sprats are metaphors for the development.

Meat trolleys 1994.

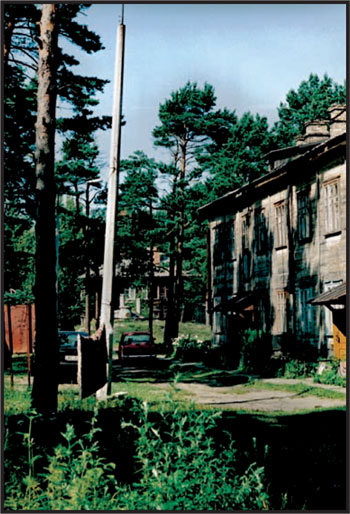

Ventspils 1993: A Russian naval base and a harbour city, definitely not showing off its potential of being a pearl of the Baltics.

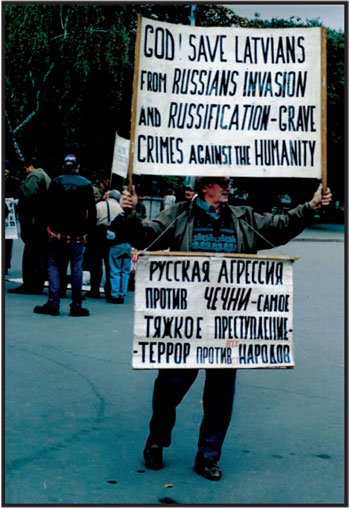

Riga 1998: From time to time nationalistic hard-liners carry harsh messages about Russians around, placards obviously meant to be read and photographed by visitors, as they are pretending that a furious conflict is going on, which indeed is not the case. Note also that the text meant for Russian readers is even more specific, as it hints at the Russian engagement in Chechenya.