Through the traveller’s eyes

There were no road signs on the spot where we had come to a halt with our car.

It was July of 1993 and my wife and I had decided to explore some of the Latvian countryside. We had hired a car in the airport. I protested immediately in the rental office, but a posh German car was the only vehicle available. I was pretty sure that it would emit wrong social signals out there, and so it did. A luxury car with Riga licence plates, who might be those exploiters visiting us? Quite right, but only after an immediate explanation, smiles came up. We met friendly people, although they were not so used to Westerners travelling around in Latvian cars, just in order to see and to talk and for nothing else.

Changes in Latvia in the years between the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the joining of the European Union were appalling in most aspects, at least on the surface. Let us throw a glance on just tourism as an example showing that changes often require deeper and broader shifts in modes of thinking than can be seen on the surface.

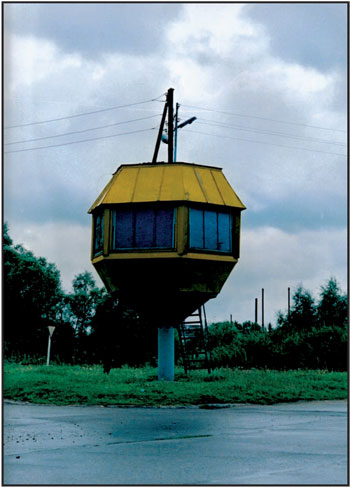

But back to the place in the countryside where we had slowed down the car with ambiguous feelings, as there were no road signs. Would the road to the left or the road to the right lead us to our destination? Admittedly, the road crossing was equipped with a control post with a tower. But the post was abandoned. Nobody was there. The time for control posts was over. The tower was a Soviet relic.

Of course we found our way in spite of the lack of signs. We had been out travelling before. However, already this detail revealed to the visitor some important traits of the Latvian society of those days when it came to tourism and migration: If you do not travel so much around yourself, and if there are only few strangers coming by, you do not need so many signs. To the newcomer, villages and cities might have looked dead and introvert at the first glance, because of the lack of information and signs. But that was on the surface.

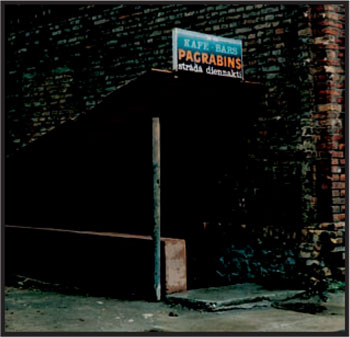

Another example: One other day in 1993 we were driving through the small city of Tukums west of Riga. It was luncheon time, and we felt hungry. No signs pointed to a restaurant or a café. Then we walked around in the city centre using our noses. I still recall the smell of fried meat which guided us into a cosy café with tasty food. Of course the local guests having their meal together with us did not need a sign to find their way.

This detail also was an indication of the fact that Latvia in the Soviet period only had very little individual tourism in the Western sense. As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, group travelling was developed to a certain degree, and high ranking Soviet people came to relax in the resorts of Jurmala or Kemeri at the Riga bay* The colourful development and history of these resorts can easily be searched on the internet.. But tourists strolling around on their own were scarce.* Hall (1991) gives a comprehensive and authoritative review of tourism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Although Latvia here is included in the Soviet Union and thus not among the national studies presented, the book is a must for the understanding of the topic. Culturally this is important, because the ever flowing stream of tourists being a natural component of daily life in most Western countries means a continuous transfer and exchange of information, knowledge, attitudes and habits.

Economically, tourism also implies a transfer of economic values, as the foreign travellers leave behind a value which is part of the national product of their own country. Therefore, in a country like Latvia, and especially in the rural areas, lack of a developed tourism is a trait which at least in the 1990ies was a significant denominator for the living conditions of the population.

But in order to be able to cash a return from visiting travellers, you have to have something to offer them – and what you offer has to be in line with preferences and interests held by the foreigner. Geographical literature* See e.g. MacCannel 1989 and CM Hall 2005. is occupied with the linkage between touristy attractions and the «markers» leading to them. In order to build up tourism, you have to define attractions, produce «markers» to them and provide facilities for guests to reach them and enjoy them. «Off site markers» tell about the sight to see and create expectations, while «on site markers» lead to the attractions where expectations will be fulfilled and the guest will be satisfied. An example: You read about the famous fountain on some romantic market place in the newspaper or in the tourist guide book. Upon arriving in the village your curiosity and anticipation will increase as you follow the signs through the narrow streets, until you are sitting there, watching the sprinkling water and a vendor offers you some souvenir to bring home as a memory and as a proof of where you have been. This is a tacit game played in all countries where tourism has settled as an industry creating income and cultural contacts.

When hesitating at the road junction outside the city of Bauska south of Riga that summer day in 1993, my wife and I in fact were led by an «off site marker», a book we had read on the Rundale Castle, a summer palace built by the Duke of Courland Ernst Johann Biron 1736–1740 and finished 1765–1768, where since 1964 a museum had been gradually built up, until major plans for a rejuvenation started 1972. Now we were looking for an «on site marker» to show us the way.

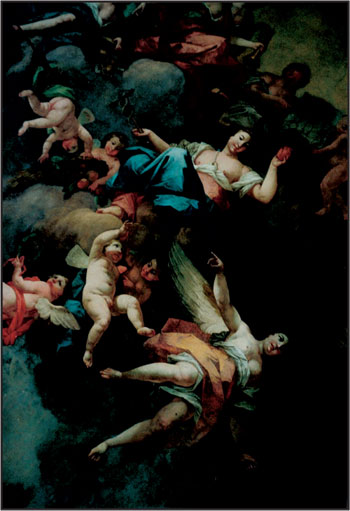

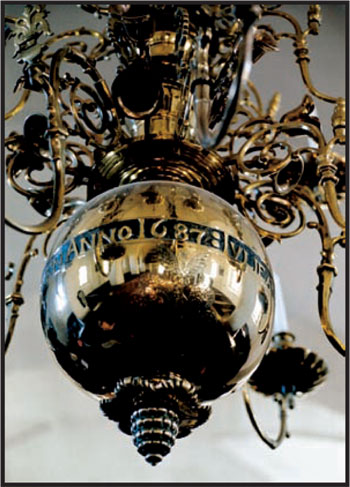

At the end of a gravel road we arrived at the fairy tale palace, built by the famous St. Petersburg Winter Palace Architect Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli, an estate then in 1993 still with decaying facades and its former garden of 74 hectares filled with weed and wilderness; one could have expected to find Sleeping Beauty here* Lancmanis 2001. The impressive two wing building was then, by 1993, still wearing scars of having served as a local school, as a storehouse etc. Restoration work was in progress with due respect for history and for tourist potential, but still the development of «markers» and infrastructure lay behind* Some time later I hired the banquet hall at Rundale for a small international meeting, at that time obviously perceived as a somewhat strange idea on the local level, but the success proved the potential of the palace also in the conference market.. However later, in the course of the years between the two unions, the Palace at Rundale settled as a national treasure and a major attraction. Buildings and park are again showing off 18th century affluence and elegance. No Sleeping Beauty here, but perhaps Cinderella is sitting at the kitchen fireplace?

Abandoned traffic control tower 1993.

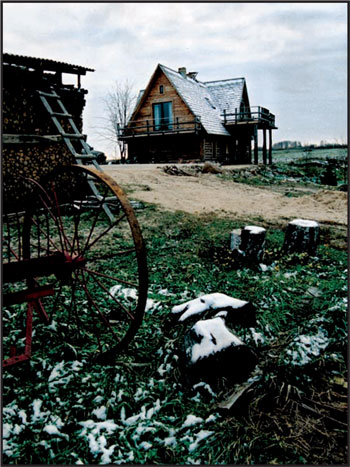

Building up a farm tourism (Ludza 2003): Rooms for rent.

Bauska cellar café 1993.

Among the many guides to Latvia, one book should be especially mentioned: A Latvian publisher and editor, the former medical doctor, anaesthesiologist, and politician Peteris Apinis has given a lavishly illustrated survey of the Latvian country and society* Apinis P. Latvia: Country, nation, state. (Riga, undated).. Curiosity awakens whilst reading it, but to the visitors and to those who might make a living from servicing them, still the full exploitation of potential seems to be limited.

Let us look at two other examples: The Eastern part of Latvia, the Latgale landscape, can offer beautiful examples of nature. There are also cultural attractions, such as the catholic monastery and cathedral at Aglona. After the revival of church life in post communist times the site attracts scores of pilgrims in August every year. But places to stay overnight and even cafés are still more than scarce. Another example: If you in 2003 should want to go for a trip to the point in the forest where the borders of Belarus, Russia and Latvia join, and where a monument in polished stone commemorate the partisans of the Second World War, you had to hand in a copy of your passport some days ahead and you had to know somebody who could make an appointment with a couple of border officials to walk with you on the path to this quite special tourist attraction, which has been made more exclusive than it deserves because of the formalities.

In 2004 two students at the Norwegian School of Hotel Management submitted a thesis on a topic from Latvia for their Master of Science degree* Rupeiks & Johansen 2004.. Their objective was to study small tourist enterprises in the Kurzeme region of Western Latvia which had been selected for EU support. Apart from the specific findings, their thesis pointed to the potential which is inherent in development of tourism for future prosperity and cultural development in rural Latvia.

Why take up this example from tourism when dealing with living conditions and health? It illustrates that there are several underlying processes which deserve attention and which are part of the background for the development of living conditions, health and health services. On the quite basic level: Freedom gives potential for travelling and commuting, but on the other hand, market economy has made public transport in sparsely built up areas unprofitable and in many places impaired the service and added to the difficult situation for the local population.

When touring Latvia in 2005, the differences between Riga and the rural districts are still remarkable. On the one hand the metropolis with its elegant city centre, cultural life and modernity, on the other hand a countryside where a depressive mood often seems to persist, and where apparent potential for a better living could have been better exploited. Often, changes in living conditions simply seem to require shifts in the baseline logic of society.

Draudzibas kurgans – partisan memorial stone on the border mound where Latvia, Russia, and Belarus meet (2003).

Rundale Castle in decay 1993.

A national treasure is restored: Part of Rundale Castle under rehabilitation 1993.

A dream about the past – ceiling painting in Rundale Castle 2001.

Layers of history – corridor in Rundale Castle 2001.

Aglona – a potential for pilgrimage tourism (2003).

Lauciena parish church 2000: Revival for the churches.

Old church valuables are displayed again (Lauciena 2000).

Vita Jostina in Latvia Tours is promoting her country for visitors from abroad (2002).

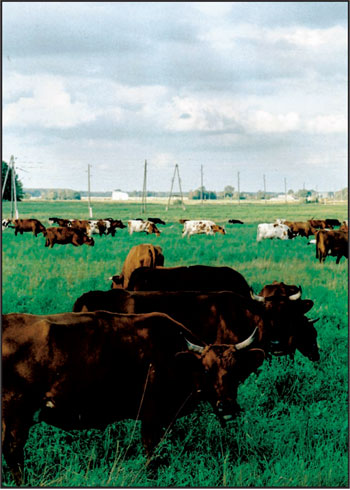

Near «Uzvara kolkhoz» south of Bauska 1993.