A museum project following the introduction in 2004 of new Norwegian legislation forbidding smoking in restaurants

Michael 2005; 2: 236–43.

Taking an initiative

In 2004, the Akershus Fylkesmuseum (Akershus County Museum) embarked upon a museum project following the New Anti-Smoking Law coming into effect* The project has been financially supported from the ABM-utvikling, Statens senter for Arkiv, Bibliotek og Museum.. The museum did a photographic documentation, collected various items related to smoking, and conducted research work on the topic. The museum project has so far resulted in some popular articles and a touring exhibit* “Da det ble ute med røyking inne” by Kirsten Linde, Akershus imellom, nr. 4, 2004. “Giftig historie” by Caroline Hambro, ABM, utgitt av ABM-utvikling, nr. 1, 2004. The exhibition “Røyking forbudt” can be lent from Akershus fylkesmuseum.. Research articles about the project and a comprehensive internet website are coming soon* The internet website “Historisk røykeprosjekt” was released on the www.kulturnet.no in the first months of 2004..

Scene from a pub before the new anti-smoking law. The smoke is hanging low in the smoking zone. (Photo Camilla Damgård, Akershus Fylkesmuseum 2003.)

Why would a regional museum take an interest in a new anti-smoking law coming into effect?

The Akershus Fylkesmuseum has specialized in research concerning the present day time. It is also a part of the Norwegian contemporary museum network* Information about the Norwegian contemporary museum network is to be found on www.maihaugen.museum.no/samtid. The purpose of contemporary museum projects is to document circumstances and collect items that illustrate central topics from contemporary everyday life. The chosen topics are often in flux, constantly changing. Concerning the new anti-smoking law, we were able to foresee a social behavioural change in at least one fifth of the Norwegian adult population. From an indoor social setting, often consisting of food, drink and conversation around the table or at the bar, smokers would now have no choice but to go outside to smoke. We were curious about this change in social behaviour. How would smokers react to the new anti-smoking law? What effect would it have on general viewpoints regarding smoking? We also took a great interest in preserving items connected to smoking in an interior setting, such as ashtrays and no-smoking signs from bars, cafés and restaurants. And we wanted to do a photographic documentation of the smoking behaviour that would soon be against the law. We knew that this documentation would be historical evidence the moment the new anti-smoking law came into effect on June 1, 2004. After this date, the documented historical smoking behaviour would be prohibited.

The new anti-smoking law

The first Norwegian anti-smoking law came into effect in 1973* Ot.prp.nr.23 (2002-2003), Sosialkomiteen Lov om endringer i lov 9. mars 1973 nr. 14 om vern mot tobakksskader (røykfrie serveringssteder).. Since then, the law has been amended on several topics concerning smoking. The new amendment in §<[FO]>6 is in everyday parlance referred to as the new antismoking law. Coming into effect, the law means that:

Smoking is not allowed where food and/or drink is served.

Bars and restaurants are not allowed to provide special rooms for smokers.

Smoking is allowed in outdoor areas, as long as smoke doesn’t filter in to the indoor area.

Owners of eating and drinking establishments must enforce the smoking ban.

The purpose of the new anti-smoking law is to protect employees and others against «second-hand smoke» (passive smoking). It was not conceived to reduce smoking. But Dagfinn Høybråten, the Norwegian Health Minister at the time, announced that it would be a positive secondary effect if smoking was reduced. Therefore, pro-smokers have claimed the motivation behind the new ban on smoking to be ambiguous* Examples from the discussion in: “-Røykeloven fører til røykekutt” VG Nett, 26.12.03, “Rettstilstanden under den nye røykeloven” feature in Aftenposten, 28.05.04 and “Forskar stumpar røykelova”, NRK.no 15.04.04..

In shopping centers smoking zones often looked as cosy small huts. These interior buildings do no exist anymore. (Photo Camilla Damgård, Akershus fylkesmuseum 2004.)

The practical accomplishments of the museum project

The author was in charge of the museum project. The main responsibility was to conduct research on the topic and to collect items related to smoking and various documentations about the enforcement of the new antismoking law. The collecting of documentation concentrated primarily on the media interest generated by smoking as a hot topic: features, smaller articles, columns and debates in newspapers and on television. The project has attempted the not inconsiderable task of balancing the views of both pro-smokers and opponents of smoking.

From May to July 2004, photographer Camilla Damgård was engaged in pictorially documenting smoking behaviour both before and after the new law came into effect on June 1, 2004. The focus of this pictorial documentation has been smoking behaviour in indoor public places: the smoking zones in cafés, bars and restaurants. And smoking behaviour in exterior public places: shopping centres and sidewalks in front of cafés, bars and restaurants. It was also of importance to the project to document the smoking zones themselves, interior installations that were removed after June 1. On May 31, the photographer was especially busy. Many smokers were gathering in bars and restaurants to «celebrate» the last cigarette in an indoor public space.

Although the photographer made a great effort to inform potential subjects about the project, she was often met with rejection while attempting to get permission from those who would be in the documentary pictures. Many smokers did not want to be shown while smoking. Only after discovering that the photographer was a smoker herself (and one of their own), did some of them agree to take part. We interpret this reaction as a result of the perceived condemnation and stigmatizing many smokers have experienced over the last few years.

Smoking viewed as a public matter

Thirty years ago smokers «ruled» the air in cars, trains, homes, waiting rooms, workshops and offices. Smokers often paid little attention to others – neither children nor adults with asthmatic or allergic reactions to smoke. Restrictive smoking laws have slowly crowded out the smokers and smoke from public indoor places. Smoking behaviour has undergone great changes, as has our view of those who smoke.

It seems as if health, both as an abstract concept and as a personal experience, has taken over as one of the fundamental ideas that establish and legitimize the Norwegian modern society. To heal, care for, protect and prevent illness and health problems in the general population, the Norwegian society has built up a large healthcare system consisting of hospitals, doctors, nurses, health experts etc. Comprehensive systems of this kind are not solely based on scientific and practical knowledge derived from experiences and research, but do also tend to have a moralistic and ethical side. The health system’s biggest aim is to protect the people against health problems for the benefit of the people. Therefore it is in moralistic terms expected that the people are working together with the health system in this common project.

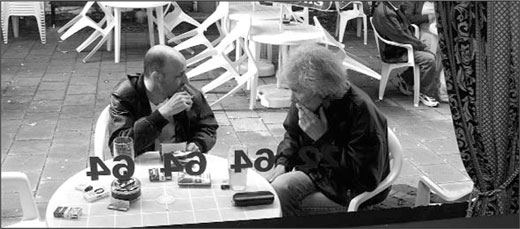

Three friends in a smoking zone in a shopping center. They eat, drink, smoke and talk. (Photo Camilla Damgård, Akershus fylkesmuseum 2003.)

In many ways, smokers do the opposite. They reject the idea of health, they damage their own health and they endanger the health of others by exposing them to second-hand smoke.

If we use the classical theory of danger and purity developed by the social anthropologist Mary Douglas, we will see that smoking behaviour and smoke in many ways fit into her description of a pollution danger* Mary Douglas “Purity and Danger”: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo, vol. 2, 2003.. Smoking as a phenomenon is equivocal. It is a kind of danger that consists of both positive and negative feelings. Positive for the smoker, who equates it with being together, drinking, eating and relaxation, and negative for the nonsmoker, who equates it with dependence, bad odours and health risks. For non-smokers, the smoke is easily recognized but it is difficult to control. The smokers are among us, they are our friends, our family. To get rid of the pollution danger, the non-smokers can use two strategies:

1. Affect the smokers to quit smoking.

2. Contain the smoke in a given area or banish the smoke from the social space altogether.

The two strategies described above were put into practice when the new anti-smoking law came into effect, the accompanying debate including a wide spectrum of positive and negative reactions.

On the evening of 31. mai 2004: The last sigarette before the new anti-smoking law comes into effect. (Photo Camilla Damgård, Akershus fylkesmuseum 2003.)

Newspapers engage in «conversation» on the subject of smoking

The amount of information in the media on the topic of smoking, not to mention the accompanying debate on the subject, paints a picture of a conflicting theme that holds great interest for many Norwegians* We have concentrated our interest on three types of newspapers by systematically collecting all kinds of articles etc about smoking in: Aftenposten (nationwide), VG (tabloid), Romerikes Blad (local) and followed up smoking themes of interest in other newspapers and television.. Theoretically, we consider the media to be leading a kind of unending conversation on behalf of the population. In their own kind of face-to-face conversation, the newspapers operate on a broad scale of expression – sometimes the tone is serious, sometimes it is angry and combative, and sometimes it is gossipy, ironic or humorous. Smoking as a theme has been examined in a multitude of ways.

The media has paid close attention to the new anti-smoking law from the very beginning. At that time, the debate dealt with lofty questions such as fresh air seen as a human right versus the personal freedom to smoke.

Soon after the law had passed, the focus turned to questions of a more practical nature: What effect would the law have on the catering trade, the night life, the behaviour of smokers? In this phase, many articles dealing with other countries and their experiences with anti-smoking laws appeared. The range of articles painted a broad scenario from doomsday prophecies to positive expectations. From time to time, newspapers printed statistics for diseases caused by smoking and the ongoing decrease in the number of smokers. The amount of articles escalated during the month of May. Many newspapers started up their own health series on how to quit smoking. A climax was reached on the evening of May 31. Television and print media had flocked to restaurants and pubs, on hand to report from the last cigarette smoked indoors. The days following June 1 went by in a peculiarly quiet atmosphere. Many predictions did not come true at all. The smokers did not protest and the effected service industries seemed to adjust to the new conditions. The newspapers looked for violations of the new law but hardly any occurred. As autumn set in and temperatures began to fall, new themes relating to smoking emerged in the media. Some establishments began to suffer financially, while people had to stand outside in the cold weather if they wanted to smoke. Many newspapers printed articles about creative and more or less legal solutions to bypass the restrictions of the new anti-smoking law. All of these solutions were prohibited by the authorities soon after.

A survey of the new anti-smoking law coming into effect shows much noise in the media but a quietly practical transition to new conditions for smokers in restaurants, bars and cafés. The apparent general acceptance of the law is interesting from a research point of view.

Many initiatives have worked together to make this change in social behaviour through legislation possible, including scientific evidence of the risks of smoking and second-hand smoke, and the belief in health as a superior goal for the good life. This creates a great interest in protecting against dangers that can damage the body. Smoking is offending the idea of health and is increasingly looked upon as a shameful dependency. Many smokers react with resignation, powerlessness or anger. One of the main reasons for not protesting is probably the sense of guilt. People who feel ashamed or sinful do often not consider their own arguments to be worthy in a conflict. With ever more restrictive anti-smoking laws, the individual freedom to smoke has been sacrificed for the sake of public health, which in turn displays a fundamental change in the values that shape our society’s way of thinking. Smoking is not simply seen as the smoker’s private concern, but as a form of pollution that causes problem for others. Consequently, smokers are met with restrictions and moral condemnation. This final point has perhaps been one of the most influential circumstances in leading to the general change in smoking behaviour.* Harald Hauglie, Akershus fylkesmuseum has assisted by the translation.

On June 1, 2004: Two of the regular customers smoking outside their favourite pub. (Photo Camilla Damgård, Akershus fylkesmuseum 2004)

Akershus fylkesmuseum (county museum),

Strømsveien 74, p.b. 168,

N-2011 Strømmen

kirsten.linde@akersmus.no