Country living in a suburb: The aspect of health in 19th century Norwegian villa architecture

Michael 2005; 2: 244–51.

Introduction

The idea of nature as a place of recreation is an important part of the Norwegian culture. The concept of nature, or rather looking at the great outdoors as something particularly Norwegian and something healing, was a central part of creating a specific national culture towards the end of the 19th century. Even today, when being asked what they like the most about their city, the majority of the Oslo inhabitants are bound to reply «the forests» or «the fjord». The favourite qualities of their city are exactly the features which are in contrast to the idea of urbanism itself. In 2005, celebrating the centennial anniversary of the dissolution of the Swedish-Norwegian union, being in contact with nature is still regarded as an important way of keeping or regaining your health, physically as well as mentally. The growing enthusiasm of the Norwegian landscape in the latter part of the 1800’s, as well as a new interest in folk art, old wooden architecture and ancient customs, coincided with the industrial revolution and a new mobility towards the larger cities. In a country desperately searching for a national identity, the fascination of the past was combined with a new awareness of science, health care, social problems, living conditions and international relations. Moral and modernity defined the period. All aspects came together in the introduction of a new type of dwelling: The villa.

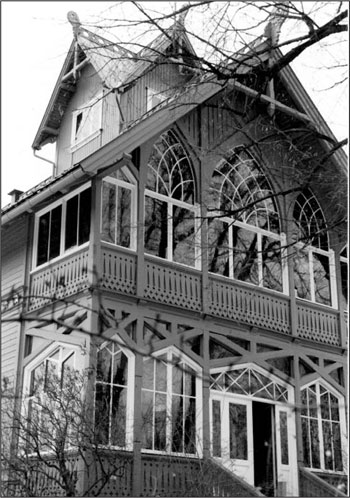

The glazed veranda of the Augustenborg villa gave a stunning view of the fjord from the inside, and beautfied the garden scene on the outside. (Photo Bjørn Vidar Johansen)

A new ideal of living

The introduction of the villa was closely connected to the construction of the Royal Palace in Christiania (now Oslo). Completed in 1848, the classical Palace introduced a completely new chapter in the architectural history of the country. Using modern building materials, prefabricated elements and importing craftsmen from abroad, the Danish-born architect, Hans Ditlev Franciscus Linstow (1787–1851), was very much orientated towards the newest principles of European architecture. Linstow chose the Pompeiian style for many of the interiors of the Palace, with one important exception: The walls of the waiting room, leading into the King’s reception room, were painted as to give the spectator a feeling of sitting inside an open, wooden pavilion. Looking out on spectacular, open landscapes through green vines and vegetation, the room was the first major manifestation of the coming Norwegian national romanticism. More important in this case, however, was the statement that the painted panoramas should calm the nerves and give the guests a feeling of relaxation and harmony before facing their King.

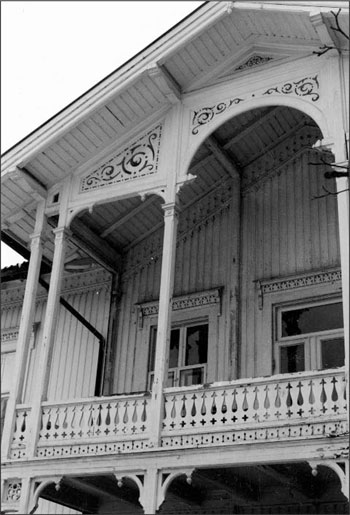

A faded beauty aside the fjord. Open verandas like this one supplied fresh air to the afternoon tea. (Photo Bjørn Vidar Johansen)

When visiting Germany, Linstow became interested in the idea of the villa. In Berlin, groups of villas had been constructed, surrounding the various palace parks. Here, their main purpose had been to create a picturesque effect, but soon the idea had developed into the establishment of suburbs at the edges of the city. Many of these villas, along with cottages, stables and pavilions, had been built in the so-called Swiss style. Long roofs, reaching over the porches or verandas, gave shelter of the hot sun or the rain, making it possible to enjoy the fashionable afternoon tea or hot chocolate outdoors. The new industrial methods of producing glass resulted in larger windows than ever used in dwellings before. The rooms were spacious and airy. The completely new way of planning and arranging rooms were largely influenced by the British and their special interest in home planning and living conditions. Instead of the French én-filade, rooms in a row without corridors, the rooms of the villa were now arranged around a central hall. This gave new opportunities of running a more specialised household, where the functional aspects were developed, as well as stimulating the idea of having special rooms for the various activities. The new plan was instrumental in the development of the idea of separating private and public spaces in our homes. It also contributed to a new concept of morality, of the secluded, of the secret, not at least regarding sexuality. However, all of this was very closely connected to the idea of keeping the rooms clean, both physically and symbolically, and thus keeping a beautiful and healthy lifestyle. This revolution in mentality was fundamental for the housing policies of the 19th and 20th centuries, and is even today, at the beginning of the 21rst, the basis of most building projects.

In modern time, the importance of the villa garden also originated in Britain. In fact, the concept of a villa is so closely connected to a garden that it can’t really exist without it. If a broad vista shouldn’t be possible, a large garden, or the view over many gardens, would give the feeling of being in nature. Spending time outdoors, growing flowers and vegetables and enjoy green, aesthetic surroundings represented important qualities. The villa and the garden were often planned as a whole. The building should add beauty to the garden scene. When indoors, or at a veranda or a balcony, the garden should add beauty to the view and fill the air with a scent of flowers.

An instant success

After having returned to Christiania, Linstow started planning a Guard’s House as well as a villa for the poet Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845), situated in the Palace park. Executed in 1843, these still existing buildings were not only the first true examples in Scandinavia of the wooden Swiss style, the villa was also the first of the picturesque, suburban kind that would soon appear in and around the major Scandinavian cities. Linstow soon erected a group of villas at the edge of the park, very much influenced by current British town planning. The closeness to the Royal Palace, the picturesque architecture and the romanticism of the era made the area an instant success. According to Linstow, the Swiss style was particularly suitable for a new Norwegian architecture, as he regarded it to be a refined version of the traditional, ancient wooden farm houses one could find in the countryside and the distant mountain valleys. Whatever a resemblence or not, the Swiss style turned to be the most popular architectural style for almost a century to come, being used for everything from farm houses to railway stations, schools, hotels, bathing resorts, hospitals and not at least all the sanatoriums erected by the end of the 19th century.

By the 1860’s, villas were also erected as summer houses on the island and coast of the Christiania fjord. Now, the growing middle class built their own summer houses at the outskirts of the city to enjoy the leisure of the season. Fresh air and sea water were attractive features of the chosen areas. Many of the new villas were situated close to larger bathing resorts and spas, growing up along the fjord as the century progressed. These fashionable resorts with their various more or less scientific programmes were instrumental in the new awareness of personal health. Soon the villas also dominated the hills surrounding the city and its fjord, following the new railway lines which made it possible to work in the city, but live in the country. The benefits of the countryside could be enjoyed all year. As their present European counterparts, and the ancient Romans (the word «villa» itself being a roman word, meaning «countryside retreat») long before them, the people of Christiania now saw the villa as an ideal way of living. Newspapers were full of complaints about the pollution, dirt, noise and low morals found within the crowded city. The recent concept of the nuclear family would need protection from these dangerous factors. The first suburban villa areas, depending on the services of public transport, were born. One of these was Ljan, a local community south of Christiania, enjoying a stunning view over the fjord.

A room with a view

By the 1890’s, more than fifty wooden villas had been erected in the steep hills of Ljan. They were all in different variations of the Swiss style as well as the fashionable Dragon style, expressing a need to develop the former into something more «national». Quite a few where prefabricated. The Norwegian parliament actively supported the exportation of these houses, focusing on the healthy and practical way of living they represented. At Ljan, all of the villas had at least one veranda or a balcony facing the fjord in the west. Often one of them was glazed, making it possible to enjoy the view longer than in the actual summer season. Many of the villas had also balconies facing north, a welcome resting place during hot days, as well as porches and garden pavilions.

Linstow’s Guard’s House introduced the Swiss style to Norway and Scandinavia, resulting in a building boom of architecture associated with both tradition and development. (Photo Bjørn Vidar Johansen)

The quick general acceptance of the veranda as a natural part of a home was very much due to the period’s strong belief in the healing effects of the fresh air. At the same time it represented a new, semi-private space, both for relaxation and informal entertaining. The three hotels at Ljan, all built in the Swiss style, made a great point of the quality of the air in their advertisements, boasting it had both the benefits of the sea and the forest. Particularly the refreshing smell of pine trees were often mentioned, hinting on its antiseptic qualities.

The healing smell of pine trees was also mentioned in an autobiography written much later by Margarita Woloschin, a Russian artist attending the lectures given by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) at the local school of Ljan in the summer of 1908. Stronger, however, was her almost obsessive joy regarding the view, and the light, thin air that seemed to be a part of the experience. Woloschin described the feeling of leaving her body and joining old spirits in an immense appreciation of nature. Although romantic and clearly coloured by the occasion, Woloschin also describes a meeting with Steiner. Here, he stated that it was at such places one could still feel the presence of the old gods, not yet having been frightened away by the present materialism and the industrial revolution.

Although a lot more down to earth, the villa people seem to have shared Woloschin and Steiner’s views. Letters, literature and interview are full of praise regarding the view, going as far as describing it as a source of everyday mental cleansing. It is obvious that the view was the main attraction of the area. Living with it just outside their windows made them feel privileged, special. In an interview with the paper Morgenbladet in 1935, the owners of the villa Augustenborg stated that the view and changing light had kept the couple healthy and full of energy since they bought the house in the 1890’s. It comes as no surprise that all of the villas at Ljan were facing the fjord. The functions of the rooms were arranged more to take advantage of the view than to meet contemporary conventions, making some very unusual exceptions from the period norms.

Pleasing the Health Council

On the contrary to popular belief today, the building restrictions were harsh during the latter part of the 1800’s. The architect’s plans would need approval from both the local Building Council, as well as the Health Council. These two bodies had no interaction, and the architectural trade papers were full of complaints about the time-consuming arrangement. Some architects claimed that pleasing the Health Council took more energy that actually designing the buildings.

The large, existing correspondence between the owner of the villa Augustenborg at Ljan and the Health Council is particularly interesting. Buying the house in 1897, the new owner Mr. Holm wanted to gradually construct a new wing, as well as improve the light conditions and comfort of the villa. The Health Council was very strict regarding any change which might prevent the supply of fresh air to the rooms. Also, the restrictions regarding indoor bathrooms and toilets were very hard to meet. Special tubes had to be constructed for airing, even in a bathroom without toilet, and the tubes would have to end far over the roof top. Such functions should also be placed as far away from the other rooms as possible. The plan of installing a toilet next to the dining room was absolutely not permitted. When Mr. Holm wanted to move the kitchen to another part of the house, the instructions from the Health Council were clear: Under no circumstance would there be permitted any changes decreasing the level of fresh air, and thus hygiene, of the room.

A comparative study seems to point to the fact that the health councils were particularly strict regarding the construction and remodelling of villas, each one object of a thoroughly consideration. One explanation is of course the large amount of villas being erected during the period and thus its domination of archives today. Another is that the authorities, through the villa movement, saw a new possibility of securing better and lasting living conditions for a growing middle class, while at the same time fighting possible epidemics on a larger scale.

Conclusions

The success of the villa was due to one main factor: The ability of being both the answer and the solution to some of the period’s many challenges. However, the immediate success in Norway is closely linked to science, romanticism and the new fascination of nature. The villa could adapt its design and location to fit the idea of the outdoors as a space for recreation and health. Now, nature was regarded as an important part of the Norwegian culture and identity. The suburban villas themselves were transformed into the same concept. Being largely constructed in the Swiss and later the Dragon style, they personified a somewhat national continuity between the traditional and the modern.

The awareness of health issues was very much a part of this modernity. Fresh air seems to be regarded as the solution of many problems. At a place like Ljan, however, the view was the main attraction. This is particularly interesting, as it points to another awareness, that of the mind, and how taking pleasure in nature could benefit the general health of the body. Of course, there was also the underlying question of morality: Being surrounded by unspoilt nature in an airy, beautiful villa would keep you heart and mind pure, too.

And why not?

The glassed verandas of the Christiania villas gave plenty of light to the interiors. (Photo Bjørn Vidar Johansen)

Reference:

Johansen BV. «Slikt stimulerer, holder oppe…» Villaen som bygningstype. 1800-tallets trearkitektur på Ljan utenfor Oslo tolket på bakgrunn av internasjonal bygningshistorie, ideologier og lokale fysiske og sosiale rom. Dissertation in Art History, Department of Archeology, Art History and Conservation, University of Oslo, 2001. (With bibliography).

Museum of University History

University of Oslo

Box 1008 Blindern N-0315 Oslo

N- 0316 Oslo, Norway

b.v.johansen@nhm.uio.no